Architectural history for gamers 2b: mountains and misdirection

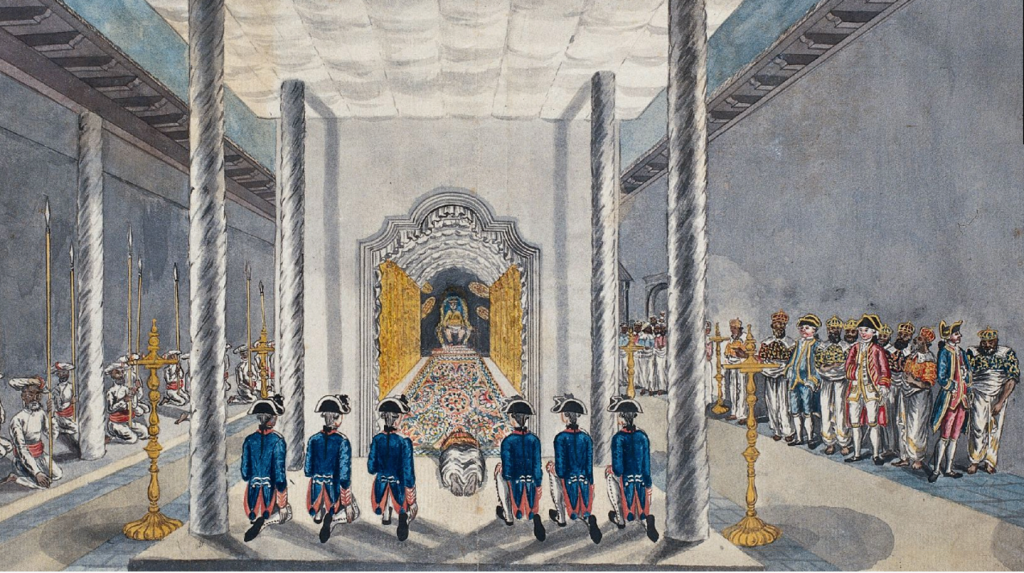

So last post we’d finally got to the throne room at Kandy and discovered that maybe the god-king actually isn’t who we need to talk to. He sits there, absolutely immobile, a mysterious silhouette on a throne at the end of the ritual garden, while various courtiers tell you what he wants and how you should be bowing and scraping. What gives?

It turns out the god-king is supposed to make everything work (everything – the sun rising, the tides going in and out) just by being. Or by his Divine Will, if you want a kinda-Christian gloss on it. And so it’s vitally important for him to never lift a finger, because that would look like taking action, which is not what he’s supposed to do.

Typical PCs in this situation look around the room to see who’s really in charge – some back door or chink in the armor that can let them break into the system and make off with the loot. And Dutch East India Company officials are absolutely typical PCs. This whole throne room setup is not useful to them – you came on a pilgrimage to see a god on Earth and you got this close to the mystery, but the final veil cannot be pierced? Try telling that to the Company directors. Therefore it must be false.

And it turns out the throne room landscape is kind of a misdirection – the people who really have power are the various groups of Buddhist and Hindu priests who speak for the king and maintain the religious traditions on which the king’s power depends. The king might actually be powerless, or might be a player among players, or might be secretly running the show in spite of his immobility, but the priests can do things. A very similar situation existed in Bali during the same period, BTW – there, the real holders of power were the Buddhist priests who (can you guess?) …controlled the flow of water down the mountain.

And they need an enormous amount of water to operate – you have to flood them to germinate the rice, and then dry them out for the growing/ripening season

So how can the king of Kandy balance the power of the different priestly sects? This is where James Duncan’s book on the subject really comes alive – he gets into the court politics and the competing discourses on which court power depends, and the arena in which the power struggles play out, and in the end it’s all about landscape design.

See, everyone has a stake in the king being accepted as divine – all the different priestly groups want a stable kingdom (with themselves at the top, naturally), and that means a king that agrees with the story they’re telling in their temples. Water is life and it is right and proper that the lake (or reservoir, actually) should be next to the palace – that wave-swell wall is a reminder that “the crown adorns the kingdom, as waves adorn the sea.” But past that, everyone wants different things. The Buddhists want Kandy tobe more like the ancient Empire of Ashoka, when the water was kept for the welfare of all, and everyone came to the Buddhist temples for education. So their ideal king would open up the lake and the temples for public access and would teach the kids Buddhist scripture, and incidentally keeps the Hindus down as second-class citizens. The Hindus, on the other hand, want the kingdom to be like other Hindu kingdoms on mainland India, with access to water and temples reserved for the privileged classes, the water being nicely channeled into walled parks and gardens, the better to echo the park-like top of Mt. Meru. In their view, the lake, temples and king should all be a bit distant from the common people, tucked behind the palace walls.

Now, a canny king would play these interests off against each other, alternately favoring one faction or another, or managing to please everyone a little bit with signs that could be read favorably by any group. So he walls off part of the lake beside the palace, and makes a garden for the Hindus to enjoy, but the other shore of the lake is open access to the Buddhist commoners. Or he sequesters a shrine behind a palace canal but puts a big Buddha statue on the hill above it, or he makes rich garden apartments for the Hindu aristocrats but puts them some miles outside the center of the city, so that the aristocrats feel guilty about not staying there. And the result is an ambiguous landscape full of contradictory signs, where making a change anywhere could lead to a shift in the balance and re-reading of the signs everywhere.

The South Indian Mayamatam Shastra (a sort of architectural manual that tells you how to construct everything from a garden to a kingdom) says “if the measurements of the temple are in every way perfect, there will be perfection in the universe as well.” Which is a great way to keep all your religious advisors haggling about temple measurements, while you get on with ruling and raising taxes and waging war and peace. On the other hand, “if the king swerve ever so little from righteousness, the planets themselves will desert their orbits… rainfall will diminish, all life on Earth will cease,” which is a great way to keep your king in line.

The last king of Kandy was not particularly canny. He came up with a sneaky plan to imprison the Hindu aristocrats in a new, highly desirable set of mansions, but in selling them the idea, he also wound up walling off the most important Buddhist shrine – so his scheme of trapping the Hindus in a gilded prison just looked to the Buddhists like giving their rivals a load of gold, stolen from themselves. He demanded that Buddhist peasants do the building work and took Buddhist temple lands away to expand the lake… with the intention of rebuilding things to restore the balance later. The whole plan might possibly have worked out in the Buddhists’ favor if it had been completed, but… the Buddhists understandably saw the raw ditches being dug and the disorder in the city and a wall of earth going up around their Shrine of the Buddha’s Tooth, and… they complained to the English (who had replaced the Dutch on the coast), that this bad Tamil king was cutting down their sacred trees and creating “great mountains of earth… a place where dogs and foxes defecate at night.” Worst of all, he had built a giant monstrosity of an octagonal tower for viewing elephant races or some other such Hindu-inflected nonsense:

The very order of the world was under threat. Perhaps the English could step in and mediate, restore order, and put the king in his place?

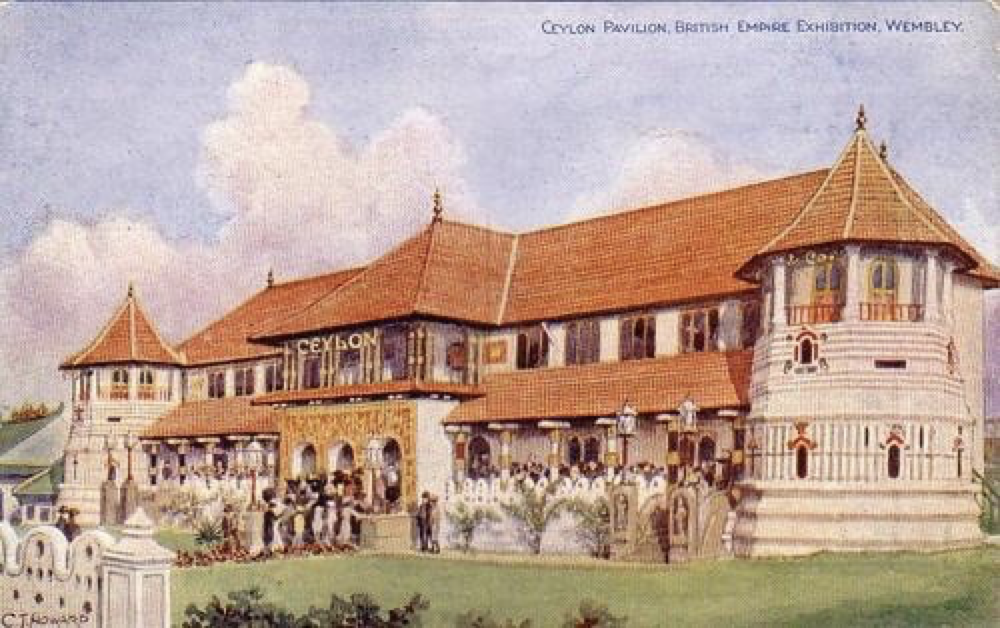

The English, of course, didn’t care about any of that. They wanted cheap and reliable cinnamon delivered to the docks down in the coastal city of Colombo, and to spend as little time in Kandy, where the cinnamon grows, as possible. So they brought in troops and put down the king, and then put down the Buddhist elites, and set up a cinnamon extraction factory, and then chopped down the bodhi trees to make room for a tea plantation, and nobody got their lake or their mansions. They could have their Temple of the Tooth, though… once its keepers had lost their right to landscape the kingdom.

So how do you use all this in games? The first thing is, if landscape communicates, then it can also lie – or at least have multiple interpretations. Potemkin villages, carefully-framed views that have wanton destruction just outside the picture, presentations that conceal the true nature of things – Lewis Mumford said the weakest regimes tend to have the most solid-looking buildings. The second thing is, landscape is no more static than anything else – it may be expensive to dig lakes or flatten hills but landscapes also change by having different people living in them, or by being imagined differently. Whom does it serve (and whom does it flatter), when you put up or take down a wall, bridge, or dam? Access to water and farmland and streets and markets can raise some communities up and push others down. Power over the people generally involves some power for those people – and nothing makes people feel ignored and aggrieved like an imposition thrown up on their land. Forts and churches want to be able to see each other, to send signals and know that all’s well between them – what happens when you put an obstruction in the way?

To take an example from fiction, one of my favourite moments in the recent Westworld TV series is where we discover the Great Designer has been designing a whole new corner of the kingdom, with a giant bucket scoop excavator hidden over the ridge of his ersatz Western wilderness park. It’s a literal case of politics via landscape – he’s taking back control of his creation from his creations.

It’s an old joke that killing the dragon and looting its hoard will tank the local economy by flooding it with gold – but what about the land developers that were being held at bay by the prospect of being barbecued? Or the cult that can now “reclaim” their holy mountain? Or the cult that has lost their nightly firework display, that proved God was still on their side? The pilgrim routes that are disrupted, the royal roads that can now cut across the goblins’ swamp? Which provinces and ethnic groups will profit, which will be pushed up into those suddenly-open mountain pastures, forced to dig bits of dragon-glass out of them so they don’t lacerate or mutate their sheep, while the Emperor’s retired Elite Guards swipe all the fertile, long-fallow farmland? If you knock down the black monolith on Druid Mesa, how will the aliens know where to park on the next planetary alignment?

Of course, the state of politics can be expressed in a hundred ways. But the power of landscape is, it’s always there. And if it changes, you immediately know about it – when something is rotten in the state, it leaves marks on the countryside. And vice versa.

…I guess I’m just repeating what Lorenzetti said in the 14th century with his murals, the Allegory of Good and Bad Government, for the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena.

-

March 14, 2024 at 6:57 pmWind, Sand and Stars: reconstructing Dune pt. 1 | Richard's Dystopian Pokeverse