Archive

Coda: when to set the Arthurian Nights

Writing the last couple of posts made me realize that there’s a bunch of similarities between the Arabian Nights stories and Arthurian legends:

– both are loose collections of stories bound together by a frame or core story;

– both had major popular revivals in the 19th century, based on important manuscript collections from about 500 years ago;

– both have some stories that are supposedly older than anyone can remember, with an oral tradition that allegedly predates the oldest written record;

– both contain stories that are self-consciously set in the distant past, compared with the “present” of their telling;

– but aside from some specific characters, that distant past setting is exactly like the storyteller’s present, like performing a Shakespeare play in modern dress.

It turns out they’re not unique in having this set of characteristics – you can say most of the same things about the Odyssey, Norse Mythology and the Bible.

And it struck me especially that, as readers, we tend to be bad at separating the explicit setting from the context of the stories’ recording – that mythical “long ago” when Arthur was king vs. the 15th century when Malory writes about him. That is, there’s a lot of handwringing about when the historical Arthur might have existed and whether it’s appropriate to dress his knights in plate armour, or whether the Arabian Nights are really set at the time of Harun al-Rashid or if they occupy some kind of Orientalist Unchanging Ahistoricist Fantasy Asia.

But considering them as literature, it doesn’t matter. The stories don’t care – they’re about personal temptations and overweening ambition and trusting to God/fate and the set dressing is strictly just set dressing.

But but but… all that said, there are remarkable coincidences of period: Harun’s Baghdad occupies the late 8th century, which is sorta vaguely Arthurian but more exactly it’s the time of Charlemagne, the king with Paladins and the Horn of Roland and so on. And the Syrian manuscript of the Nights is pretty much contemporary with Malory. And the 19th century revival tended to excite the same people: those Pre-Raphaelites who loved to paint the Lady of Shalott also loved Orientalist subjects. (By now we know William Morris was all over this stuff, right? His whole decorative arts career was like half Euro-medieval, half Indian prints)

If Arabia seems a long way from Chivalric Britain, it didn’t to 19th century British authors and artists. The disordered England of Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe depends on the absence of Richard the Lionheart, who was off defending Christendom from the Saracens in the Third Crusade, leaving wicked King John to usurp the kingdom (and those loyal royalist Cornish were supposedly ransoming Richard with “bezants,” or so they said a century later). Bringing the Crusades home to village scale, Ivanhoe teams up with Robin Hood and a disguised King Richard against John’s crony, the wicked Sheriff of Nottingham, whom we know is wicked because he stayed home rather than fighting with the Crusaders.

As is typical for Victorian medieval women, she’s making a tapestry. Or maybe embroidering. Women and cloth, weaving as female power. And the messenger disquiets her with a piece of decorated cloth, maybe something she made? Maybe Richard’s baldrick.

For another Anglo-Chivalric/middle Eastern mashup, Pre-Raphaelitist Dante Gabriel Rossetti liked to riff on the imperial, the patriotic, and the personal by painting himself in the guise of St. George, patron saint of England, together with his wife Elisabeth Siddell (or other paramours) as the Egyptian Princess Sabra, whom Richard Johnson had created to be St. George’s wife/reward in his Elizabethan-era retelling of the George-and-dragon myth, Seven Champions of Christendom (1596).

This Sabra doesn’t look much like Elizabeth Siddell, who is much more typically Pre-Raphaelite in the 1862 version, painted just before she overdosed on laudanum.

So there’s your Shining Armour Orient, right there – the East feminized, England her protector, etc. etc. There’s a 19th century Occidentalist gaze to hang beside the Orientalist one, too: the 1835 Arabic-language Boulaq recension of the Arabian Nights introduces post-Crusading Christians in the form of piratical Genoese villains, who capture and sell Muslims – which is a neat echo of that Orientalist cliche about Barbary Corsairs enslaving white women. (To get a sense of just how big a cliche this was and how much 19th century western Orientalist artists and viewing publics loved a bit of slave-erotica, check out this enormous and exhausting catalogue of pictures of odalisques and slave girls. NSFW in parts. None of them are actually pre-Raphaelite, though, as far as I can tell).

So what to do with all this? First, it’s interesting to note that the non-historical Islamic world of the 1001 Nights partners very neatly with the non-historical England of Arthurian romances: both sets of stories were being compiled at the same time and both regard their own times as tragically fallen compared with the earlier golden ages they choose to remember. During Malory’s life, Britain was being torn apart by the Wars of the Roses and he dreamed of a uniting Arthur, to heal its divisions. At the time of the Syrian Manuscript, the unifying Caliphate of Islam was a distant memory and Caliph Harun was an emblem of a lost purpose for the overall community of believers. In both story cycles the “present” landscape is a patchwork of petty kingdoms, robber knights and false courts… so it’s easy enough to imagine characters traveling from one to the other and maybe finding there the key to their own kingdom’s renaissance. Although maybe the least interesting approach is to throw in a lone lost wanderer, like Nasir in Robin of Sherwood. It might be better to invert the viewpoint and have your party be the foreign wanderers (fresh off the boat, to borrow Tekumel’s cliche) in the newly strange deserted forests of Albion – like in The 13th Warrior. If you want to mix in the 12th century Crusades but not from the usual jingoistic perspective, check out ibn Munqidh‘s memoir – and if you want to know how to get from Chretien de Troyes’s France to the Holy Land and back by way of Norman Sicily, there’s no better sourcebook that ibn Jubayr’s Travels. Personally I’d be tempted to mix up Antar with Arthur and start a picaresque comedy of errors.

Or do a points of light campaign across the known world, tied together by a quest for the Holy Grail or a lost Excalibur. Grail mythologies have long toyed with the idea of a Templar network linking East and West, so your Arthurian Grail Quest could go… well, at least as far east as Persia – maybe Alamut, with a stop-off at Ararat to tangle with antediluvian dinosaurs or djinn. If you go with an 8th century Charlemagne/Harun axis, you could run all the way out to Talas to fight or trade with T’ang Dynasty China and pick up some of their high tech printed paper, prophetic fortune-telling cards, and automata.

Another approach would be to run with the sheer variety of the stories – Arthurists tend to emphasize a unity to the corpus but it’s really very varied, with phantom islands and faerie kingdoms and strange visions in the mists. From the Red Knight of the North and his parody Camelot to the lost lands of Lyonesse, Ys, and St Brendan’s Isle, there’s plenty of room for different interpretations of Chivalry, politics, and even geography. Add in the meddling of Arabian Nights djinn and scheming witch-princesses, Mount Qaf with its underground mountain chains and ibn Majid‘s world map with a hollow pole and you can have your knights explore (or pop up from) tunnels through any inconvenient genre space in the known or mythic worlds. Give the players al Idrisi’s map of the world and let them deduce where the hex boundaries are. To really mix things up, locate either the Arthurian or Arabian world inside a djinni’s brass jar, so that one map can travel around the other, making impossible trouble and swallowing up whole towns along the way.

So far I’ve only been messing with the set dressing, rather than really getting my teeth into the thematic cores of the two story-cycles. I’ll be honest, I have a harder time imagining either Arthurian prophecy or the Arabian Nights’s humble fatalism as suitable material for building RPGs around. Man’s helplessness in the face of fate and/or God’s plan can make for good stories with surprising endings, but how do you make them interactive? What handles do they offer players to grasp, to make their own destinies?

And most of my ideas involve keeping the two setting flavours somewhat separate, or seeing how they mess each other up, rather than making a synthesis out of them. Still, with a slight reskin, they can definitely be made to play well together – imagine a story where a bold princess is imprisoned by her evil father, the masked vizier of a hidden sultan. Fate draws her toward a trusted old servant, who happens to be secretly raising the Once and Future King, her brother. And the only way she can communicate her peril is through two unprepossessing servants, one a dwarf, the other a pompous halfwit. It turns out both the Arthurian and Arabian Nights romances have plenty of stories for a family drama like that, requiring princess rescue and the destruction of the evildoer’s fortress.

You can probably even come up with some spurious scientific-sounding jibber jabber to justify a flying carpet race through the halls of the Sultan’s palace, to find and shatter that one vulnerable jar that contains his heart.

Bèton Breton

At Adam Thornton’s request, a quick review of some English and Breton brutalist structures.

I cannot find any credits for the architect or engineer who devised this, nor for the landscape designer who made it such an iconic ritual object. It’s currently regarded as “infrastructure porn.” Welp, give it a decade and people will start to celebrate it, or not.

Brest, in Brittany, was heavily bombed during WW2, so there’s a lot of postwar reconstruction. This church and the one following seem unusually interesting, to me at least. One recalls the Dutch “maritime modern” school of Amsterdam, the other has the reticulated look of a Berlage design.

Brutalism for God continues into the 21st Century! The interior shots (click the links) make it look calm and meditative and less like a piece of electronics packaging.

I never even imagined that Ian Fleming might have named a villain after a postwar Hungarian-British architect, but apparently: “A discussion on a golf course about Ernő with Goldfinger’s cousin prompted Ian Fleming to name the James Bond adversary and villain Auric Goldfinger after Ernő—Fleming had been among the objectors to the pre-war demolition of the cottages in Hampstead that were removed to make way for Goldfinger’s house at 2 Willow Road. Goldfinger was known as a humourless man given to notorious rages. He sometimes fired his assistants if they were inappropriately jocular, and once forcibly ejected two prospective clients for imposing restrictions on his design… Goldfinger consulted his lawyers when Goldfinger was published in 1959, which prompted Fleming to threaten to rename the character ‘Goldprick’.”

But he didn’t. Everyone backed down, the film went ahead, and humourless Goldfinger forever afterward had to answer annoying, irrelevant questions.

You can also rent another bunker in the chain for holidays, if you feel like feeling like a Nazi artillery spotter for a week.

Pre-Raphaelite Arthur part 2

Last time I talked about some reasons why I think 19th century versions of Arthur have been ignored in RPGs. The core of my interest is really the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – a loose collection of British artists and writers who shared a certain artistic sensibility in the middle of the 19th century, who promoted a distinctive view of Britain’s medieval history and who shared an enthusiasm for rich decoration; hand-worked, non-industrial art; and thin, red-haired women. They mostly knew each other, at least through the critic John Ruskin, who promoted their exhibitions, and William Morris, who did everything – fine and decorative arts, writing, organization, editing, promotion, sales… You could decorate your whole house with Morris’s work, from the furniture and wallpaper to the books on the shelf and painting in the study. So what happens if we actually look at them?

Well, there’s really a bunch of subjects all tied up together here:

– the differences between Tennyson’s 19th century Arthur stories and Malory’s 15th century ones;

– the visual storytelling of the Pre-Raphaelites and its influence over our “look and feel” for Arthurian type stories;

– the whole idea of the “medieval world” as a setting.

Taking the last part first, both the concepts of a medieval and a renaissance period were invented after the fact – first in the mid 16th century, to differentiate the then-improving present from the crappy past, and then in every time period since, to support narratives about the present. The idea of the medieval is based on a story that says Europe (and therefore “civilisation”) had been glorious under the Roman Empire but then it was plunged into darkness on September 4, 476 AD by the Goths, and there is stayed as a cesspool of disease and depravity for a thousand years, mired in a “middle age” between two golden ages. Roman civilisation was finally “reborn” (“re-naissance”) – in Italy, of course – and could first be recognized in the form of a new naturalistic skill in painting.

This story started as an art history theory and spread to other disciplines. The idea that visual arts can offer a barometer for cultural sophistication is central to the whole concept: if people can paint with perspective then, art critics reasoned, they must have maths, rationality, and improving public health. And to this day, hardly anyone really questions that equation. By the late 18th century Edward Gibbon, having noticed that early Christian art had turned Rome away from perspective and naturalism, blamed the spread of Christianity for screwing up the Roman Empire and depriving the world of working sewage systems.

The period of “rediscovering” ancient Roman glories and learning how crap Europe had been without them is obviously tied up with the 17th and 18th century “Enlightenment” movement (a term actually used by people at the time!), which can perhaps be summed up in the sentence; “now we’re no longer superstitious medieval idiots and we can finally think for ourselves, how shall we take charge of the world?” Maybe less obviously, this same period also saw European colonialism and early imperialism spread across the world. In the late 17th century, Europeans started thinking of themselves as superior not only to their medieval ancestors but also to other peoples – in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. The similarities in developing attitudes regarding the medieval past and the Orient are… striking, such that by 1800 I don’t know if either idea really makes sense without the other – Orientalism is the practice of viewing Asians as medieval and anti-medieval prejudice is a kind of Orientalism. In the second half of the 18th century European critics start calling Indian society “medieval” and “child-like” – an attitude that only strengthens right up through WW1.

But then in the 19th century, several things come together to give this Enlightenment confidence a bit of a jolt (outside France, at least) and swing the pendulum… somewhere else. First the French Revolution, which started by killing aristocrats and ended by crowning a commoner, made a lot of aristocratic rich Brits rather nervous. The rationalist French Republic had collapsed into a military dictatorship, just like the Roman Republic had (Napoleon even had a habit of dressing up as Julius Caesar, just in case you might have missed that historical echo). After Napoleon’s capture in 1815, “Romantic” movements started to question the Enlightenment’s confidence in engineering every aspect of the world and humanity – if it led to dictatorship, maybe it wasn’t so desirable? The best-known expression of this counter-movement is probably Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, with its over-reaching scientist and dispossessed, sympathetic “monster” offering a pretty transparent critique of turn-of-the-19th-century society. In visual art there’s less imitating Greece and Rome, more striking dramatic poses and expressing (horny, restless, heroic) emotions.

Right: Anne-Louis Girodet: Chateaubriand Meditating on the Ruins of Rome, 1808. Thoroughly Romantic. Note how his powerful meditations ruffle up his hair, giving him a windswept and interesting air. He’s thinking “even mighty Rome could not escape the inevitable dissolution of all worldly majesty.”

Second, there’s a rise in nationalist movements all over Europe. Nationalism is a sort of religion that claims the people of this territory are different from and better than those next door. This territory’s people must therefore rule themselves independently and define what makes them so awesome. That awesomeness almost always comes from the incalculable past, maybe the beginning of time itself, and is generally found in the soil, the blood, and the spirit of the people. It tends to suddenly burst out in revolutions, where you can finally see it waving free and shocking the formerly powerful but now degenerate imperialists who were holding it back.

Third, there’s a big Gothic Revival movement over much of Northern Europe and especially Britain after about 1850, which strangely rehabilitates the medieval, bringing it into the growing nationalist mythologies.

Late 19th century buildings in Germany, Canada, and England. Source.

What? Weren’t we just clawing free of our medieval constraints? Well,

(1) those primordial nationalist roots are eternal, not constrained by the changes of time, so it’s hard to be proud of your Nation in perpetuity while also being ashamed of it before a couple of hundred years ago, and

(2) I have a sneaking suspicion it is not accidental this rehabilitation happens at the same time that “scientific” racism becomes fashionable. During the 19th century, discourses of colonialism get more racialized (at least in Britain, France, and Germany), so that colonized people are seen not so much as “backward” but as “fundamentally inferior.” Scientific racism allowed for a decoupling of anti-medievalism from colonialism, i.e. it allowed you to be both Orientalist and enthusiastic about the non-Roman bits of your history at the same time. And

(3) rapid industrialization was irreversibly reconfiguring the landscape and society of Britain and the British Empire worldwide, in ways that made it significantly less amenable to Romantic celebration. It turns out “rationalizing” business into Capitalism doesn’t spontaneously create a sort of neo-Greco-Roman ideal world. So a bunch of British intellectuals and aesthetes started pining for a simpler time before the Neo-Roman imperial movement began… or maybe they were just sick of Enlightenment neoclassicism, or maybe they wanted to show that Britain had always been great, even through its supposed “dark ages” before it rediscovered Italian civilisation.

If this sounds anti-progressive, yeah it is, although its proponents would insist they just wanted to be smart about progress and not simply accept whatever changes happened to be happening. The Gothic Revival movement was also often semi-self-consciously fantastical: they tended to decorate garden follies or make new building types – like railway stations – look reassuringly medieval on the outside while doing nothing to disguise their Dark Satanic Mills on the inside. When Gothic Revivalist Pugin contrasted the “best” of the medieval world (very often heavily idealized) with the “worst” of the Enlightenment – juxtaposing e.g. medieval almshouses with enlightenment Panopticon prisons, he deliberately glossed over the better comparative cases – medieval punishments and enlightenment charity like he wasn’t even trying to win an intellectual argument.

As I mentioned last time, you draw your boundaries where you want, to yield the specific effect you prefer. The Pre-Raphaelites drew their boundary right at the cusp between the late medieval (early Renaissance) and the High Renaissance, just before the church lost its near monopoly on approved subject matter for paintings. They decided that British painting had been cruelly hijacked and made to serve Classicist Italian models ever since Sir Joshua Reynolds had started up the Royal Academy of Arts, because Joshua felt that everything could be improved by adding ancient Rome – he thought painting had returned from the dark ages under the brush of Raphael and that Rubens and Reynolds himself were Raphael’s successors.

I dunno, personally I’m not totally convinced Reynolds was up to Raphael’s standard...

Sick of the Italian High Renaissance contraposto and chiaroscuro lighting that Raphael had championed, and sick of the slavish Classicism of the Royal Academy’s judges, who preferred eg. Jacques Louis David to the Pre-Raphaelites’ own Edward Burne-Jones, the Pre-Raphaelites formed a Brotherhood to celebrate the awkward poses, meticulous costume detail, and flat picture planes of the painting world that Raphael had ruined.

Their excitement about rediscovering a medieval sort of sensibility was not strictly historicist, though. They definitely said they wanted to strip away years of Enlightenment/Baroque nonsense to reveal a purer/more spiritual essence… but they didn’t want to excavate the past: instead they were interested in improving it – creating a more perfect, more authentic medievalism for their current moment. You can see the same impulse in Viollet-le-Duc’s restorations of e.g, the fortified medieval town of Carcassonne, where he harmonized the appearance of the conical roofs and added a drawbridge here and there, bringing the city, as he said, “to a complete state that may never have existed at any one time.”

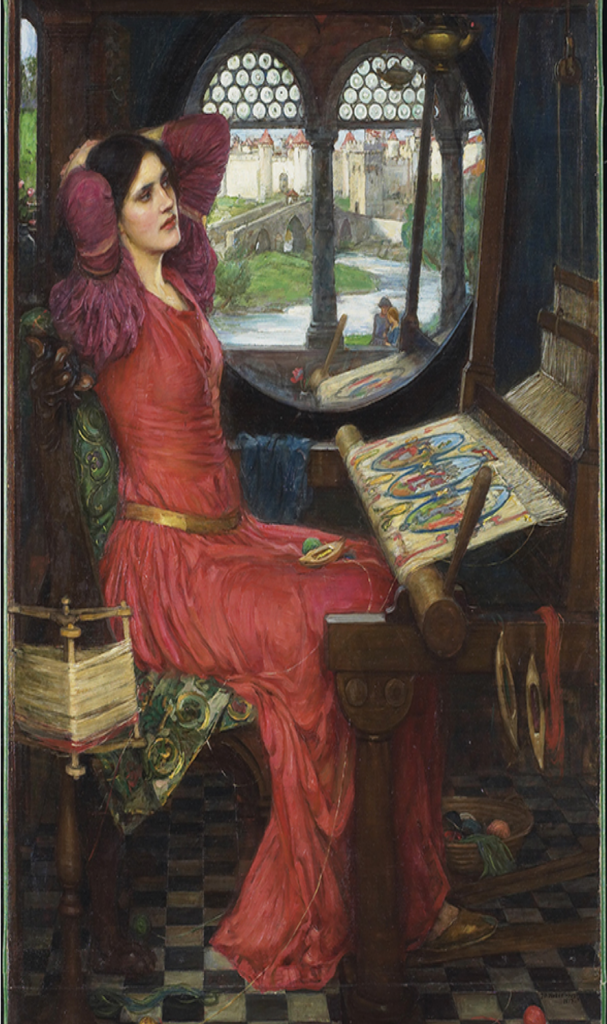

Pre-Raphaelite painter John Waterhouse puts Carcassonne in the mirror behind Elaine of Astolat (a.k.a. the Lady of Shalott), a minor character from Malory who plays a much larger role in Tennyson’s 19th century Idylls of the King. She is shown here tied up in her tapestry-wool, an apt metaphor since in Tennyson’s poem, merely by leaving her womanly position at the loom, the Lady dooms herself to death. BTW I’m pretty sure that’s William Morris’s loom, that Waterhouse’s model is posing beside.

The sheer number of Pre-Raphaelite paintings of the Lady of Shalott is daunting. Evidently, they found her to be Tennyson’s most compelling subject.

OK, so. Tennyson. When it comes to a more perfect medievalism, it’s pretty interesting that Tennyson chose Malory’s Arthurian myths rather than, say, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales as his window into the period. Both are works of literature, so neither should really be trusted as guides to their originating societies but… Chaucer drew portraits of many of the social types of his times, he was interested in peasants and millers and landowning ladies, alongside the more conventional knights and squires. He wrote about their concerns regarding marriage and wealth and poverty and birth and death and farting. Malory’s world, on the other hand, only really consists of knights and ladies, knights and quests, knights and false robber-knights. Tennyson’s main contribution is to refocus Malory from the knights onto the ladies’ experiences, retelling the stories as dramas of women and presenting those women as products and victims of their station. When people talk about the miserable state of Victorian gender politics, chances are they have Tennyson lurking in the back of their minds.

So when Sir Lancelot-the-Heartthrob uses the “favour” of Elaine of Astolat to joust and gets injured, all to defend Guinevere’s reputation, what Tennyson writes about is Elaine falling in love with Lancelot while she tends his wounds, Lancelot ignoring her (for honour and because secretly he loves Guinevere), and Elaine dying of a broken heart. Note, even though this is Elaine’s story, her agency in it is restricted to loading herself into a boat and clutching an accusatory love letter to Lancelot, so that her dead body drifts down to Camelot and her story is finally heard posthumously, causing the court to weep.

…if you were writing an RPG about Chaucer, you would need massive sourcebooks about all the various walks of life and society. You’d want varied character classes and backgrounds etc. An RPG about Malory (other than Pendragon) might be best served as a limited-frame storygame, where the players take the two roles of Knight and Lady, and the quest objects and background are generated ad hoc. A game based on Tennyson’s Idylls of the King would probably be single-player storygame (the Lady), with the object of getting Arthur to understand anything about your life, with nothing but flowers to communicate your meaning.

Hey look, there’s another set of roundels like the ones she was weaving, only this time they’re quilted.

Gustav Dore (not a Pre-Raphaelite) also illustrated Tennyson’s Elaine, in a style that makes her look less tragic and more consumptive.

Aside: I think (and I expect I’m in the minority here) there’s a recognisable German-ness to the Dore illustrations. I add them here because I think the contrast with the Pre-Raphaelite depictions really points up how distinctive the Pre-Raphaelite vision is: the expressions and attitudes of the women, the attention given to their material culture, cloth, embroidery, jewelry, etc. and the equal attention given to “foreground” and “background” elements all suggest a larger world that extends beyond the canvas – far more, I think, than Tennyson’s poems demand.

Of course, if romantically-painted Victorian women aren’t swooning tragically, they’re vectors for sin and witchery… which I have to say, the Pre-Raphaelites really enjoyed. The villainous old gossip Vivien follows Merlin to a remote place across the sea and seduces then curses him, taking him away from Arthur’s side so that Arthur can enter his tragic final phase.

Morgan le Fay, Arthur’s witchy sister, when painted by Frederick Sandys embodies all sorts of exotic dangers, suggesting a much wider world than Malory knew:

Birmingham Museum’s label (as recorded on Wikipedia) notes that Morgan le Fay is shown “in front of a loom on which she has woven an enchanted robe, designed to consume the body of King Arthur by fire. Her appearance with her loose hair, abandoned gestures and draped leopard skin suggests a dangerous and bestial female sexuality. The green robe that Morgan is depicted wearing is actually a kimono” – so, still intimately involved with cloth and weaving, but this time weaving Arthur’s downfall!

There’s another aspect to this layer of Arthuriana, though, that I think is part of that unavoidable frame the 19th century hangs around our vision of the past. Note the Egyptianate figures on the wall behind her, the vaguely Indian-looking statuette, the magical devices on her gold dress. Also, check out the spear that wicked King Mark uses below to strike down Sir Tristram in Ford Madox Brown’s contemporary Arthurian painting, the death of Tristram/Tristan:

Where did King Mark of Cornwall get a Chinese (or Japanese?) spear? Is that an Indian dagger in his belt? What about the Turkish (or Persian) designs on the curtain behind him? There’s a clear Orientalist presence in these paintings – certainly around the villains (the heraldic Bezants that identify Mark as Cornish were supposedly gold from Byzantium paid to the Saracen for Richard I’s ransom, so they’re Oriental twice over, while still being Cornish…). But even the very unvillainous Lady of Shalott’s death-shroud in Waterhouse’s painting, above, suggests an Indian Chintz, the subject of London’s great 18th century Oriental fashion craze (which BTW started that neo-Gothic trading palace, Liberty’s of London – purveyor of William Morris fabric prints).

I think the intention of this Orientalism is probably atmospheric rather than ethnist or strictly imperialist – my sense is that the pre-Raphaelites’ perfected medieval world contained the riches of the Orient, that in our inadequate history only became visible to the British around the time of Elizabeth I. The moral lessons they sought to draw from Arthurian legends demanded setting in silks and jewels – like the ones from an ancient crown that Tennyson has Arthur distributing to his jousting champions.

As for that famously shiny armour, about 10 years after the Pre-Raphaelite painters made their mark on Arthur, a (sometimes) Pre-Raphaelite photographer added hers: Tennyson invited Julia Margaret Cameron to create another illustrated edition of his Idylls of the King in albumen prints.

Cameron used whatever props she could assemble for her photos. Here, Arthur and Lancelot are wearing Crimean War cavalry helmets, a glancing reference, perhaps, to Tennyson’s most famous poem. Or maybe there were just a lot of them lying about in the 1870s. Her Death of Arthur could be the prototype for the final departing boat shot in Boorman’s Excalibur.

I don’t think Boorman’s Excalibur is really a neo-Pre-Raphaelite film, BTW – it’s pretty clearly Wagnerian – but it’s hard not to see those cavalry helms and the very shiny knights cantering through the window of Burne-Jones’s Laus Veneris,

reflected in Boorman’s ultra-high gloss, vaseline-glowing armour:

Final aside: I note that Liberty’s of London gets a credit at the end of Excalibur for “ethnic jewelry.” If that’s not a nod to the Pre-Raphaelites, I don’t know what is.

Pre-Raphaelite Arthur, part 1: Arabian Nights, Authenticity and the Arche

Over the summer I saw an exhibition of Pre-Raphaelite Arthurian artworks, which included a couple of tapestries, now owned by Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin fame – he who took his copy of Lord of the Rings to the Glastonbury festival and (along with Moorcock) pretty much kicked off the liaison between metal and fantasy.

So I think there’s some interesting things to say about the content of Pre-Raphaelite Arthurianism but before I get there I have to clear my throat over the genealogy of Arthurian myth in popular entertainment and roleplaying circles – Arthur’s Appendix N, if you like – and why we seem to favour different ingredients of that genealogy at different times. So if you’re up for an extended musing on the history of Arthurian and British medieval representation, strap in.

While Gygax was percolating the ideas that would eventually become D&D, US popular entertainment was telling a particular set of stories about Merrie Oldee Englandeee, with Poul Anderson’s Three Hearts and Three Lions, Gilbertson’s Ivanhoe comics,

…and Disney’s 1950s anglo-historico-romance films: The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men, The Sword and the Rose, and Rob Roy.

Together, those stories form a particular view of medieval Britain that draws heavily on the 1810s to 1830s works of that inveterate romantic nationalist Sir Walter Scott, the inventor of Ivanhoe, romanticizer of Rob Roy, and inspirer of, among others, the Pre-Raphaelites and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, who wrote a whole bunch of Arthurian epic poems for them to illustrate. To get a taste of Scott’s style and how his thought was shaped by Arthurian romances, you can look at his articles in the 1824 Encyclopedia Britannica, on Chivalry, Romance, and Drama:

“In every age and country valour is held in esteem, and the more rude the period and the place, the greater respect is paid to boldness of enterprise and success in battle. But it was peculiar to the institution of Chivalry, to blend military valour with the strongest passions which actuate the human mind, the feelings of devotion and those of love.”

As for the fair maidens who excited those manly passions, they had better be chaste and pure, because “wherever women have been considered as the early, willing, and accommodating slaves of the voluptuousness of the other sex, their character has become degraded… On the other hand, the men, easily and early sated with indulgences, which soon lose their poignancy when the senses only are interested, become first indifferent, then harsh and brutal to the unfortunate slaves of their pleasures. The sated lover,—and perhaps it is the most brutal part of humanity,—is soon converted into the capricious tyrant, like the successful seducer of the modern poet.”

So you can see how 50s Hollywood might have liked Scott. His rants against “the Romish clergy, who have in all ages possessed the wisdom of serpents” are a digression I guess I don’t need to go into now. On the other hand his frequent asides on “the love of our country and its liberties” played just as well in Joe McCarthy’s day as in George W. Bush’s.

So here’s a funny thing about encountering D&D’s version of the medieval in Britain in the 1980s: that heroic Scott/Tennyson strand was deeply out of favour. Especially in its Hollywood incarnation, with shiny armour and technicolor yeomen, it provoked an emetic reaction. I don’t know exactly why Britain went all in on the Dung Ages after WW2 (although I can hazard a few guesses, based on postwar austerity and disillusionment, changing class relations, the collapse of the Empire and Britain’s prestige, etc.). I also don’t know why Tolkien seems to have been exempt from it (C S Lewis’s Narnia was less exempt: wearing its Christian and Arthurian allegory on its sleeve, it was dismissed as children’s lit). But I do know that talk of shit-covered peasants wasn’t limited to Monty Python – Holy Grail satirized a popular discourse which had obviously gone too far, but which would continue to be repeated right through the 1990s.

WFRP, obviously, encapsulates the RPG end of this mood about Britain’s past and character, but it doesn’t exhaust it: in the 70s and 80s my schooling emphasized the filth, disease, and short life expectancy of the medieval era as the bottom of a hole we had recently climbed out of. As for King Arthur, if there was any real historicity to him (and my primary school teacher was convinced there was), he was probably a Romano-British hill chieftain fighting off the Saxon invasion at the dawn of Britain’s Dark Ages – more a pitiable Alfred burning the cakes than any majestic flower of chivalry or guardian of England’s destiny.

(Aside: David Lowery’s recent Green Knight plays interestingly with Dung Ages tropes – the start of the film sees young Gawain sleeping off a hangover in a barn while the house across the muddy yard is burning. Arthur’s court is as threadbare and caveman-stark as any Trevor Nunn staging. But then Lord Generous’s tempting castle occupies a comfy Elizabethan early modernity – deviating from dung is where Gawain goes wrong, being a Son of the Soil after all)

So the Arthur I grew up with was part Monty Python, part dirt-poor resistance fighter – provided he was suitably dirty and down-at-heel. But if there was any whiff of the knight in shining armour cliche, that belonged to a discredited strand of romantic fantasies more akin to Mills&Boon bodice-rippers.

I knew there were stories behind that shiny romantic tradition (and there was Greg Stafford’s Pendragon, if you could get anyone to play it) and I knew there were images that went with those stories but… you had to kind of willfully ignore them, like in The City and The City. They were not serious or realistic or authentic (words actually used sincerely (by me!) in the 80s/90s regarding FRP rule systems).

As a result, my conception of what was properly medieval was resolutely unheroic and anti-Arthurian and I wouldn’t look seriously at the 19th century construction of Arthur for decades. It wasn’t right, it wasn’t “canonical,” it wasn’t worth bothering with: if there was any way for me to rediscover Arthur it would be by looking straight past the romantic knight tropes and past Malory’s high romantic 14th century vision (still too shiny) and trying to squint it out of Geoffrey of Monmouth and the Mabinogion.

Which was stupid of me, first because Geoffrey of Monmouth is the Dave Hargrave of the 12th century, a reliable guide only to his own inventions (at best), and second because whether I ignored it or not, the 19th century work remains instrumental in forming the frame we all look through when we look back at the romances of Malory and Chretien de Troyes. Because, let’s face it, the 19th century always sits in between whatever came before and our view of it.

So I was already thinking about ideas of authenticity and historicity when I started listening to a reading of the Arabian Nights – specifically the collection edited by Muhsin Mahdi, which claims to be “the definitive Arabic edition… the oldest surviving version of the tales and considered to be the most authentic.” And it’s an interesting comparative case.

First, the 14th century Syrian manuscript Mahdi’s collection is drawn from is not the only claimant to antiquity – its reputation rests partly on its similarity to other old manuscripts. The editor notes “no one knows exactly when a given story originated, and many circulated orally for centuries before being written down,” which makes the whole question of what’s definitive hard to even discuss. But this apparent weakness in supporting the definitive claim turns out to be a secret strength for the stories’ authentic claim: “in the process of telling and retelling, they were modified to reflect the general life and customs of the Arab society that adapted them” so that the 14th century manuscript shows “a distinctive synthesis that marks the cultural and artistic history of Islam.”

Well. Maybe. I don’t know how you would prove that and I’m wary of claims to read the soul of the past, whenever they show up. In any event, choosing to cut this synthesis off at the 14th century is an editorial power move: it sorts stories into real (14th century) Islamic culture and… not. Which is how connoisseurship always works – carving out a subject on which one can become an authority. It is intensely annoying for a collector that there should be a diverse oral tradition that they can never fully capture and master. Different collectors hold up competing “original editions,” and then publishers want to cut through the confusion, claim the high ground and put out a “proper, authoritative” version, and then inevitably someone out there literally collects 1001 stories and…

And it’s a matter of interpretation and selection because, as the translator notes, the Syrian manuscript only represents one tradition of Arabian Nights storytelling. Some time after the manuscript was made, a vibrant print culture in Egypt and Europe distributed a load of reprints and rewrites, adding tales (including, notably, The Seven Voyages of Sinbad) and generally destroying the idea of a single common core of stories. Much of this print culture happened in French, which is the first language of several early editions of these “Egyptian” stories. The editor’s decision to exclude all of these and his dismissal of Aladdin and Ali Baba as forgeries (since they were written in Paris in the 18th century, maybe by an Arabic-speaking Syrian Christian migrant, and entered the corpus initially in French translation) establishes a fence between the Collectible Authentic Object and a yawning, inclusive chaos. If you let Parisian Aladdin in, do you have to include Disney’s Aladdin movies? So the omission of Sinbad and Aladdin, perversely, guarantees the authenticity claim because why would you leave the best-known pieces out unless you had a good reason?

Muhsin Mahdi has his reasons. But it’s up to you, really, where you draw your boundaries.

With the tales of Arthur and his knights, and with their place in defining the image of a medieval world, it seems to me that insisting on consulting only authentically medieval sources doesn’t do away with the problems of what to include – ignoring Malory is silly, because he’s already done much of the work of reading old Welsh for you. The Malory and Chretien de Troyes collections are famous and long-standing but not sufficient: there’s also the whole Matter of Britain still hanging out there, only partly available to non-specialists and tailing off into Welsh and Breton myths. If on the other hand we treat Arthuriana as a living tradition and draw a wide, inclusive boundary like we would with the “Egyptian” Arabian Nights, we wind up enclosing so many contradictory creations that we lose all coherence – it becomes impossible to say what isn’t Arthurian. Which is a real problem for a medium of collaborative storytelling like RPGs, where the important thing is to generate a common understanding – some stable platform that allows you to judge which actions are genre-appropriate and what does and doesn’t fit – what constitutes a knight, a quest, and a dragon, and why those elements matter.

So let’s imagine for the sake of argument we’re after a more limited, authenticky sort of specifically British Arthur and we arbitrarily discount anything from the advent of Hollywood, since that tends to change everything to fit its own shape. Before we even get around to worrying about which side of the pale Scott, Tennyson and the Pre-Raphaelites fall on, we have to deal with Henry Tudor’s propaganda version from the late 15th century, composed just a few decades after Malory’s death. In this telling, Henry VII, as unifier of England after the Wars of the Roses, is the returned Once and Future King. He commissions a Round Table for his eldest son, Arthur (yes actually) to rule from.

Nothing Arthurian ever goes according to plan, of course, so Arthur dies in childhood, leaving his brother Henry VIII to resurrect that Round Table idea, by repainting a giant antique table he found, to present himself as King Arthur reborn.

In fact, if there was ever a real, historical person who looked and acted like a romantic, literary Arthurian knight, it’s the young Henry VIII. He loved to joust – he even set up perhaps the greatest of all tourneys to challenge the French king and knights in 1520, which makes it about the same length of time after Malory’s le Morte D’Arthur as the Lord of the Rings movies came after the book.

And he had several lovely sets of full jousting plate armour – bullet-proof and everything – made in his own Royal Armoury at Greenwich.

And he was just about the right level of deadly and doomed when it came to the women in his life, although maybe popular history hasn’t quite pieced together that jigsaw puzzle of misogyny disguised as veneration, yet. His only real flaws as an Arthurian archetype are that he got old and fat (more villainous King Mark than forever-fighting romantic lead) and that he was born too late: the 16th century isn’t quite the right period for a character whose primary chronicler died half a century before – if we still believe at all in a “right period” for Arthur.

All of the Tudors were schooled in propaganda, so it shouldn’t surprise us that during the reign of Elizabeth I, Arthur (or possibly his relative Prince Madoc) was deployed once again as the secret original conqueror of America. “The case could be made therefore that, as a descendant of Arthur and through Madoc, Elizabeth had rights to North America” – and the hated Spaniards were merely squatting on English soil.

Oddly enough, that’s not the Arthurian legend Hollywood chooses to remember. But I can’t say I blame them – the popular consensus though history has been, if you want an authentic Arthur, you have to create one yourself. Which brings us back to the Pre-Raphaelites (in the next instalment).

“O purblind race of miserable men,

How many among us at this very hour

Do forge a life-long trouble for ourselves,

By taking true for false, or false for true;

Here, thro’ the feeble twilight of this world

Groping, how many, until we pass and reach

That other, where we see as we are seen.”

Tennyson: Geraint & Enid

Sedulous Icosahedron

The dungeon walls are mortared stone, damp and mossy. The ceiling hangs heavy with calcerous drips, lost roots and fronds of lichen. In the centre of the chamber’s north wall there is a round, ragged indent in the stonework, with stones lying scattered on the floor. A single, glossily clean, roundish boulder bulges from the indent like a pustule. Peppered with thousands of gemstones of all colours and laced with thick veins of gold, it is a treasure-hunter’s dream. And colossal! It stretches almost from floor to ceiling, a geometric marvel of sharp, triangular facets.

Approaching, you see some writing is carved on each facet – the one facing directly into the room says “START ME UP.” On the surrounding facets you read “HOW DOES IT FEEL?”, “PLEASED TO MEET YOU” and “IT’S JUST YOU AND NO ONE ELSE.” A single number 1 is visible, half buried in the wall.

If the players leave the stone alone, well, they will have left the dungeon’s single biggest treasure behind.

If they hack away at the wall and free it, it rolls onto the ground and totters a little. Instead of coming to rest on one face, its rocking motion increases until it starts rolling.

It will pursue anyone who has touched it until it crushes them. Essentially, it’s like the giant rock at the beginning of Raiders of the Lost Ark, except it never, ever gives up until it is destroyed.

diameter: roughly 9′

HP: in the thousands

It rolls initially at walking speed (4mph). For every 10′ it rolls without changing direction, it can increase speed by 5mph, up to 70mph on clear, flat terrain. It always knows where its target is. If they cross a sea, it will roll across the bottom to get to them. It is immune to fire, cold, poison (obviously) and lava damage – although if it passes through a long lava field, it will emerge red hot. If it runs into an object like a door that stops it, then it backs up as far as it can and rams it again. If 10 rams don’t knock the obstacle down, it looks for another way around it.

If it has multiple targets, it pursues the nearest one. So it is theoretically possible to trap it like Buridan’s Ass.