Archive

Some Basic Anthropology Texts For DMs

I’ve been thinking about a shortlist of books that my kids would benefit from reading, and on reflection, I’ve decided just about everybody would benefit from reading them, if they haven’t already, since we all may have some time on our hands.

To get on the list, a book has to have significantly shaped my own world-view, sure, but it also needs to be generally applicable to a lot of different questions (so no books on, e.g. underwater archaeology), and it should also be fairly short and accessible and possible to summarize without jargon – so that excludes e.g. Marx’s Capital, even though I think that’s an indispensable read for understanding nearly anything written in the humanities during the 20th century, regardless of whether you agree with its arguments.

These qualities, of general usefulness, readability and clarity, tend to go together with strength of argument. The part about me being impressed by the books’ arguments… is obviously idiosyncratic. I’d be interested to see what lists others around here produce.

Looking it over, I see my list is a bunch of old, old works. This is not because I think they’ve stood the test of time or some similar conservative nonsense but because

(a) academic fashion over the past 40 years has been against clarity and brevity, and

(b) they’re pretty much all anthropology texts (or “political theory,” which is to say, anthropology minus field work), which deal with familiar topics and behaviors and yet somehow their ideas have not been absorbed into common parlance. Which makes me suspect that despite being broadly “political” in nature, they are somehow resistant to being used as political footballs – a quality that has also been unfashionable in anthropology for a very long time.

With all that in mind, and in no particular order:

Mary Douglas: Purity and Danger

Douglas gives some critical thought to what constitutes “clean” and “dirty” in different cultures, and it turns out that these categories are really important for understanding what’s considered to be “ordered” and “disordered” in society. Once you grok this, biases in e.g. Hobbes’s Leviathan spring into focus – Hobbes is not just scared of disorder, he’s also disgusted by it as a dirty thing (nasty, brutish and short), so he needs a “sovereign” (the people) to make living in the world imaginable. Applicability to Lovecraft, Oscar Newman’s “broken windows” theories, and anti-immigrant politics should be obvious.

If you’re writing an RPG campaign, this will help you understand what gets revolutionaries thrown to the lions and how to outrage the Winter Queen’s court in just the right way to free your party-mates.

Marcel Mauss: The Gift

Mauss talks in detail about a specific set of communities in the Pacific Northwest of the US and in Papua new Guinea, but his Those People Over There observations work perfectly for Everyone Around You. He says gifts are not, in the first place, generous acts of sharing but instead ways to generate socially-binding debts.* Right-wing charity organizations spring straight to my mind, but (here’s the clever bit) Mauss doesn’t stop there and he doesn’t actually disapprove of gift-economies – he sees the position of hanging debt as a basic building block of social cohesiveness. This is useful for understanding Charlie Stross’s sf story Neptune’s Brood, without having to read trendier lefty darling David Graeber’s 550pp Debt: The First 5000 Years.

Applicability to RPGs: every time a local chief or grand vizier or corporate rainmaker has a mission for the PCs, and every time they need a favor from such a character, and whenever PCs get into positions of power, you can use this kind of gift exchange to make sense of their social climbing and networks. Just find and replace “Trobriand Islander Chief” with “Mafioso.”

*obviously the gifts you and your family give are selfless acts of generosity and any anxiety you feel about not having given the right gift for the circumstances is just because you like the people you’re giving the gifts to and want to please them. That’s because you’re freed from the cycle of debt by the example of Jesus, who died for your uh oh no wait now.

Benedict Anderson: Imagined Communities

Anderson wanted to know why people fight and die for their country. He wound up writing a theory not just of nationalism but of community self-representation in general. If, in a discussion, you refer to a community as “imagined,” you can quickly identify who in your earshot is qualified to talk usefully about what communities are made from by separating the ones who nod in recognition from the ones who look angry. Unlike most theorists of nationalism, Anderson doesn’t just conclude it’s bad. When he says community is “imagined” he does not mean it’s necessarily a sort of imaginary fantasy, but rather that it necessarily must be actively reproduced in each member’s own imagination, out of various kinds of representation, which contain various arguments about power, since it lives only in collective imagination.

He’s clearer than I am, read him.

Also, there’s a delightful short excursus on the use of monuments and why official photos of them tend not to contain sightseers.

Read this for RPGs if you want to write convincing polities, patriots or propagandists. Like dirt and gifts, people tend not to want to think hard about what communities mean or how to feel about membership in them (parroting pious phrases is not thinking hard). This is a good book for getting you to ask “but what if it were different? How could it be? Has it ever been?”

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior is Almost Always Good Politics

OK I lied. This book is decades younger than the others, and a whole lot more obvious and obviously partisan in its arguments. And to be honest, it didn’t change anything about the way I think. But it’s still very useful to have it written down, so you can see its arguments clearly – it’s the book I wish I’d had available to cite during grad school whenever I was told some very complex theory about justice and history that didn’t match the data I could see. The (fairly universal) workings of power are laid out simply, cogently, and more or less in handy bulleted lists, without any of the sentimentality or partisan apologizing that just about everyone else does. To hold onto power, you have to identify and cultivate the people around you who can get things done. That means, the ones with networks of influence and debt. Sadly its newness means I can’t give you the full text, but these “rules for rulers” videos offer a handy summary. Yes, it ties together with Mauss and Anderson. And it explains little things like why democracy is unlikely to take off in Saudi Arabia (the economy there doesn’t need a helpful, educated class to agree with its rulers, it just needs to be mined). Any time someone tries to tell you how power really works, check their explanation against this ground state, to see if it’s actually doing better than the default, or if it’s just claiming some kind of spurious virtue by associating itself with other values.

Usefulness for RPGs: right in the title it tells you this is a sourcebook for making evil empires. And in fact any empires. You can use it to check the motivations of the powerful and see if they “make sense:” if you can explain what a particular governor or admiral is doing in ways that satisfy Bueno de Mesquita, then that’s enough to satisfy any cynical party of players.

The virtue of such a list lies in its shortness. There are lots of worthy works that didn’t make it in, that have ideas I refer to all the time. But this is where I would start, personally.

Maps of some classic dungeons, 3: Ramses’s linear psychopomp

Continuing the series on real-world dungeon types leads us, inevitably, to architectural narrative sequences, or railroad dungeons.

Tomb of Seti I in the Valley of the Kings. What it lacks in Jacquaying it makes up for in pedagogical clarity.

The ancient Egyptians were really hot for linear, narrative structures. Their temples and tombs have one way in, one destination, and a series of lessons to be learned along the way, so that the architecture serves as a tour guide to a state of mind, to priestly initiation, and to Egyptian cosmology.

That’s Nut, goddess of the night sky, vaulting over a sarcophagus. The walls are covered in the Pyramid Text – a Baedeker’s Guide to the Egyptian afterlife, which is itself a kind of railroady ur-campaign. More of that later.

Here’s Ramses III’s memorial temple in Luxor – not the biggest or grandest of the Ramessea (Ramses II’s the Mos’ Grandiose) but one of the best-preserved and clearest in plan:

Entering from the Main Pylon at the top of the frame, note that there’s an unbroken axis through a series of lined-up doors all the way to the back room, where the portrait of the dead Pharaoh is located.

Entering from the Main Pylon at the top of the frame, note that there’s an unbroken axis through a series of lined-up doors all the way to the back room, where the portrait of the dead Pharaoh is located.

Here, another view where you can see the commanding bluff wall and majestic-but-still-exclusive doorway of the Pylon:

The purpose of this arrangement is to allow the architects to pull several tricks – first, they can tell stories on the walls, knowing that you’ll progress through the structure in the sequence they want (and that you only get to see the punchline if you’re the right level of priest). Second, they can arrange information hierarchies off the main axis – stop at particular points along the way and you can learn the stories of Ramses’ wives and forebears, all subordinate to the main axial narrative, like hyperlinks off the main article. Third, they generate a very narrow, straight beam of light from the front entry all the way back to the holy of holies, so that if the priests open all the doors on just that one special day each year that’s sacred to the Pharaoh (which wasn’t a cliche back then), then the sun can shine all the way down the axis to the portrait on the back wall. If the temple tells the story of progressing from Earth to Egyptian heaven, where Ramses resides, then on this special day, His reflection travels back down the arduous path to spy on His people. Also, stick a load of gold and glass in that portrait and you can have it light up the whole back room, so that the special secret stories carved in there are revealed in the radiance of the Pharaoh’s visage. Theatrical stuff.

(OK I cheated, that’s from Ramses II’s tomb at Abu Simbel, but the principle is the same, or would be if robbers and earthquakes hadn’t screwed up RIII’s special moment)

My point here is that the Ramesseum, typical of Egyptian temples, limits visitors’ choices in order to expand its narrative possibilities and concretize its hierarchies. The Grand Axis points to the point of the building – it tells the faithful about the Pharaoh’s divine journey, lets them relive it as they progress inward, and tells them where they should stop, appropriate to their appointed level, in order to pay their finely-calibrated respects. Side chapels and structures are side-quests – lower in status, therefore more accessible, they appease secondary gods, hold the remains of minor wives and functionaries, and fill in bits of myth from distaff sides of the royal lineage that don’t quite merit a place in the main story or the regular attentions of a priest.

The Ramesseum offers a physical map of the structure of New Kingdom Egyptian religion, which is to say, of New Kingdom Egyptian society.* It also offers a campaign frame for Pharaohs and their subjects, with character class-specific goals:

– Pharaoh: command your country well enough that you can build a temple and tomb with all the systems working, plus a mortuary services caste (mummifiers, mourners etc), to give you gear on your journey through the afterworld;

– Wife: get enough favour and influence that you get a story spot close to the back room, giving you gear and protection on the afterworld jaunt;

– Priest: level up far enough that you get the right to go into the back room, where the deepest mana stores are held;

– Tomb-robber: collect inside knowledge that you can use to Indiana Jones it into the treasure room without getting riddled with darts/ghosts.

.\0/.\0/.\0/.\0/.\0/.\0/.

Architecture is a communicative art.

It tells you what the owner of the building wants you to think about their status and your own. It tells you where to stand and what roles to assume, what you should and shouldn’t do, where you should and shouldn’t go.

Buildings are maps of institutions.

5 military branches, 5 stabby points on the Pentagon. All equal in the eyes of God if not in funding or status. Yes I know there are serious problems with this facile example, but they’re such intriguing problems…**

Buildings are very often theme parks of their institutions’ concerns and neuroses. Where the institutions support communities, they teach their inmates how to behave, what they can and can’t do, who’s in charge.

There are lots of directions I could go here. Private houses in the era of psychoanalysis becomes maps of the mind – insights into the soul of the person who shapes them. Hence the haunted house, i.e. haunted family (thanks Jack Shear!). It’s no accident the protagonist of Inception (that celebration of memory palaces) winds up in the basement. Hence also the Romantic trope of Bluebeard’s Castle, with its doors onto a bloody treasury and a sea of tears,

and Poe’s explanatory palace of damnation and illusions in Masque the Red Death.

But today it’s the canalisation of architecture I want to talk about, and how it pertains to (railroad) campaign design. Railroads get a bad rap, especially in the OSR, because nobody wants to be pushed to make choices that are no choice at all, and nothing makes players rebel more than having their motivations assumed for them. And yet there are whole genres of play that depend on/exult in railroading. What is a Call of Cthulhu campaign but the serial unlocking of doors, leading to ever-more-horrible doors?

All plots are railroads, inasmuch as they progress through stages and there’s already something happening when the players show up. The key to good railroading is to reconstruct your pushes as pulls – goals rather than herding – and to intersperse the choice-limiting pipework with tasks that involve free invention.

The Pyramid Texts painted all over the walls of the Ramesseum offers one method – it’s a list of directions, which you have to pass through in sequence to get to your ultimate destination. So it’s a railroad with continual teases: just follow these instructions exactly and do not deviate from the path and you’ll be OK. With, of course, obstacles designed to tempt or scare you off the path. The same basic vamp is visible in Early Christian labyrinths,

where the walker is invited right up to the edge of the holy center for an early look at the goal, before being directed away again, to walk around and around it, sometimes toward and sometimes away from their target, knowing what it is and therefore why they have to jump through whatever hoops and tests of faith are necessary to get there. (Note how it’s not a maze – both medieval and classical labyrinths are unicursal: single involuted paths, designed not as puzzles but as meditations.)

This is the basic structure of any Rod Of 7 Parts type campaign: once you know you need to assemble n parts, it’s up to you to figure out how to fetch them and what the best sequence is to try (hint: do the lowest level one first). It’s absolutely a railroad, and often one where the players have to construct parts the track. Its saving grace is that the players have some freedom about how to do it, maybe digging new tunnels into the final room or fooling someone else into passing tests for them – it doesn’t necessarily matter what they do in an episode as long as they follow the bigger rails of the episodic structure.

If you really sell them on the goal, though, you can get them to hew ever closer to the intent of the railroad. I can hear DMs breathing through their teeth from here, but bear with me.

Torii gates mark the boundary between mundane and sacred spaces. Which is why they tend to work like stationary TARDISes in anime.

The point of ritual journeys is not so much to cover distance as to change the people undertaking them – to adapt them to the system of an institution. Often they require special cleansing and passages through death and so on in order to allow access to the Sacred Space where the Final Adjustment can be made. That’s why trespassing in Pharaoh’s tomb is so dangerous – partly because you trip the security systems, sure, but mostly because you’re not the right level to be there, you didn’t bring the right passes or armour. According to this scheme, Howard Carter and his friends didn’t know what they were missing, so they punched a crude hole in the cordon sanitaire between worlds and as a result started leaking secret juice. They had to be scrubbed from the mundane for structural reasons. (The way Grim Fandango presents this is rather disappointingly Christian, but maybe it points to a deeper level of initiation: the development team are not Aztecs!) And if you don’t take the long, strait way? Then there are options for dramatic moments of sacrifice – you can’t enter the garden, but you can help someone else go in and bring the paltry gold out, while leaving the mystery inside. Someone purer, more deserving. Maybe your next character. It’s your choice.

Ars Magica has a deracinated version of this Sacred Precinct idea in its regio – a higher level/excited state of a mundane location that only opens on midsummer eve or when you’re holding the hand of a fairy or if you’ve collected the 7 seals. It’s a neat mechanism for putting the end of the campaign right on top of the wizards’ home, where they were always brushing their hats against it but couldn’t access it until they were properly initiated. It allows Ararat to exist simultaneously as a literal lump of rock you can climb to get a nice view, and as a holy mountain, gateway to heaven etc. But it fails to address the bigger point of such sacred-other-spaces: by having to go on the full ritual journey to get there, the players get to understand the significance of whatever’s sacred in the campaign – the stakes, the terms of success or failure, the structure of the game.

Most great epics save this moment of realization for the end because it was what they had to say and once they’ve said it, you should be free to read something else. But as a DM you only have to stop there if you can’t think of anything the players might want to do with their secret knowledge. Effectively, it’s leveling up. If you have another campaign set in the world as it is after The Change, then congratulations, your players will be totally excited to get on with it, having sunk all those costs into being Stage 1 shlubs.

][i][i][i][i][i][i][

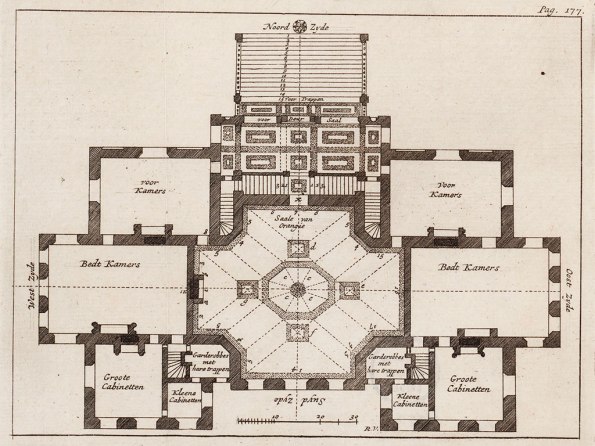

The late 17th century Dutch palace known self-deprecatingly as the Huis ten Bosch offers a neat little map of the political society that built it. It has the same basic structure as the palaces of Louis XIII and XIV, and contemporary English lords, and a whole load of other monarchs, but this one has a geometric purity that makes it all so clear.

The late 17th century Dutch palace known self-deprecatingly as the Huis ten Bosch offers a neat little map of the political society that built it. It has the same basic structure as the palaces of Louis XIII and XIV, and contemporary English lords, and a whole load of other monarchs, but this one has a geometric purity that makes it all so clear.

As a 1st level shlub (not a 0-level commoner), you might get invited to a big do in the Grand Ballroom:

and you’ll probably feel like that’s a great and special reward, but it’s only the first step on a long staircase of initiations.

floor plan – the ballroom’s the big cross-shaped space in the middle. Pretty awesome!

Out of the throng of courtiers in the ballroom, only a lucky few get invited up the stairs to the voorkamer – which can afford to look less impressive because the people there know how much more powerful everyone present is. From there, a precious few get to meet the monarch (well, stadhouder) himself, in his bedroom! Which is sweet indeed but nothing compared with being invited into his closet behind it, from which hardly anyone at all – just grand vizier level true intimates – get invited into the little closet behind that.

Leveling up here means smaller scale, deeper secrets, a different view of the realm. To be called for an interview in the little closet and subsequently to leave, unnoticed, via the back stairs means not only that you have the ruler’s full confidence but also that you are yourself secretly a member of the select band of cognoscenti – and anyone who knows it (ie only the useful few) will hang on your every word, attentive as a courtier, ready to fulfill your secret needs. To inhabit this level of society is to pass through a city outside that others do not see, but that they may be able to sense clinging to you.

The initiated recognize you as a regio.

tl:dr –

1. don’t neglect the communicative powers of architecture. If you set your dungeon up to speak to the players about the secrets they can uncover, you will supply them with a line of mission briefings that can support years of play, that the players actively want to unlock.

2. it’s tempting to keep your secrets secret – everyone loves uncovering them and writers (less often, players) love having their expectations overturned when the Big Cheese does a face-heel turn or it turns out it was aliens all along. But those kinds of secrets are only powerful at the moment of revelation. Letting them slip early makes them active parts of the campaign in anticipation. It lets you pile significance onto setbacks and shortcuts, it encourages the players to try to find ways to “cheat,” i.e. find creative solutions.

3. depending on the degree of buy-in your players are feeling, they might be up for a not-cheating path, in order to maximize their initiation level. If that’s the case you can get them to submit to all sorts of arbitrary limitations that will make the game harder and more interesting. What if using violence makes them unclean and locks the doors? What if they have to train a new generation to pass the final lock? What if only someone who doesn’t know what they’re looking for can find the key? The hard part of all these tricks is getting the players to really understand them. The fun part is watching them figure our ways to fulfill the requirements.

* OK fine, not the whole society, just the political class.

** This obvious reason is, of course, spurious. Probably. After all, in 1943 when the Pentagon was designed, there were only 4 branches. People who are too smart for this trap often say that the Pentagon is a pentagon because it happened to be built on a 5-sided piece of land, but this was (a) a strange accident, in Pierre l’Enfant’s rigorously geometric plan, and (b) no longer true by the time of construction. It suggests to me that FDR probably knew an Air Force would be set up eventually (optimally after the war, to avoid confusion mid-conflict), but didn’t want to spill this destabilizing plan before it happened. So the building is prophetic – those that had eyes (or clearance) to see, could read the future of the military in its plan.

on the costs of trade

One of the projects I’m in the middle of right now is an early-modern trading game, for which I’m currently rereading Neil Stephenson’s excellent (but daunting) Baroque Cycle.

If you haven’t read it, and you have any interest in the gaming possibilities of the 17th century, then you must go out and read it right now. If you did try to read it and found it hard to get into, start with King of the Vagabonds (which is officially “Book 2”) and then read Quicksilver (Book 1). That way you’ll immediately see the picaresque RPG potential without having to wade through obscure allusions and the Royal Society shenanigans that are Stephenson’s first love. The books can be found separately (expensive, if you want the full 8-book Cycle) or packaged together in Volume 1, which is, confusingly, also titled Quicksilver).

So the reason I’m writing is, I’ve got some rules for maintenance and wasteage, and I’ve been wrestling with whether anyone really wants them – is this the spirit of adventure? Struggling to find enough timber and tar to stay afloat? And then Stephenson points out to me that yes, in fact – the demands of running a ship pretty much dictate that you must get into risky business. Your boat is more than a hole in the sea, surrounded by wood, into which you can pour an endless flow of money. It’s also a demanding patron, which seeds adventures with every worm:

[A ship is] …a collection of splinters loosely pulled together by nails, pegs, lashings, and oakum… She floats only because boys mind her pumps all the time, she remains upright and intact only because highly intelligent men never stop watching the sky and seas around her. Every line and sail decays with visible speed, like snow in sunlight, and men must work ceaselessly worming, parceling, serving, tarring, and splicing her infinite network of hempen lines in order to prevent her from falling apart in mid-ocean… Like a snake changing skins, she sloughs away what is worn and broken and replaces it from inner reserves—evoluting as she goes. The only way to sustain this perpetual and necessary evolution is to replenish the stocks that dwindle from her holds as relentlessly as sea-water leaks in. The only way to do that is to trade goods from one port to another, making a bit of money on each leg of the perpetual voyage. Each day assails her with hurricanes and pirate-fleets. To go out on the sea and find a [ship] is like finding, in the desert, a Great Pyramid balanced upside-down on its tip.

Not convinced? Too wordy and abstruse? Want more of that GURPS Goblins flavour? Here, then – the opening lines of King of the Vagabonds. Even if you only invest in that one, it will repay you a hundredfold. A free campaign opener on page one…

MOTHER SHAFTOE KEPT TRACK of her boys’ ages on her fingers, of which there were six. When she ran short of fingers—that is, when Dick, the eldest and wisest, was nearing his seventh summer—she gathered the half-brothers together in her shack on the Isle of Dogs, and told them to be gone, and not to come back without bread or money. This was a typically East London approach to child-rearing and so Dick, Bob, and Jack found themselves roaming the banks of the Thames in the company of many other boys who were also questing for bread or money with which to buy back their mothers’ love.

The way of the mudlarks (as the men who trafficked through Mother Shaftoe’s bed styled themselves) was to voyage out upon the Thames after it got dark, find their way aboard anchored ships somehow, and remove items that could be exchanged for bread, money, or carnal services on dry land. Techniques varied. The most obvious was to have someone climb up a ship’s anchor cable and then throw a rope down to his mates. This was a job for surplus boys if ever there was one. Dick, the oldest of the Shaftoes, had learnt the rudiments of the trade by shinnying up the drain-pipes of whorehouses to steal things from the pockets of vacant clothing. He and his little brothers struck up a partnership with a band of these free-lance longshoremen, who owned the means of moving swag from ship to shore: they’d accomplished the stupendous feat of stealing a longboat.

Inevitably, they get ambitious and start cutting anchor cables, so they can loot the drifting ships at leisure – or even merely threaten to cut them, to extract protection payments. Inevitably, things go wrong and get complicated.

Need more, always more? Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor is a couple of centuries later but just as perfect.

Interlude: Cheese Guns

When I was a teen my players suddenly got heavily into gun porn. Some mix of James Bond 007 rpg, GURPS, and Twilight 2000 did it to them, and they all suddenly knew about the relative merits and problems of SA80s and M16s and H&K machine pistols. And I said “this is fetishism” and they replied “what’s the rate of fire on that M40 sniper rifle?” and “no, that’s famous for jamming, you should use this instead.” Funnily enough this was in Britain, where none of them had access to any actual firearms. It was all just armchair kung fu talk. I can only imagine what it was/is like in some corners of the US.

So I ran a Flash Gordon campaign, with cheese guns. Name a cheese – that’s the noise the gun makes when fired. Stats follow from the implications.

So a Cheddar is a slow-repeating machine gun, like a Tommygun. A Brie is a railgun with an ultra-fast rate of fire. Emperor Ming’s guards carry Gorgonzolas: freaky purple deathray blasts, weird electrical kirbykrackle around the muzzle.

Limburger.

Limburger.

Danablu.

Danablu.

All guns go “Cheshire” when being readied to fire. And (thanks Anne), a “Swiss” is a silencer, which is versatile and practical but sadly makes the damage the gun does really bland.

…they loved it. They never seemed to understand I was making fun of their gun fandom. They kept top-trumping guns in their other games, but in Flash Gordon they just took off searching for the rare and mysterious Stilton.

Mascarpone.

(PS: in those days if anyone threatened to spend half an hour telling me why their sword/fencing style was the best, I’d just grant them +1 when fighting with that particular sword. They were happy, I could get on with the game, it worked. But now we can just chorus “that’s not a talwar, it’s a nodachi!” and move on.)

(PPS: all polearms do 1d8, except those that are especially lovingly described, which do 1d10. There.)

A city is not a dungeon

Whenever I open a new RPG book, I hope for two things:

first, to be surprised by a new world I can get my imagination fired up about – some atmosphere or proposition that makes me want to play it;

second, some solid ways to get my players equally engaged with it, so that I don’t have to do all the heavy lifting of getting them to see what I see when reading it – ways to put them in the right kind of mindset to enjoy whatever it is that makes this particular book special.

A lot of city supplements are pretty good at the first task – they describe what’s distinctive about their particular city, treating it more or less like a zoomed-out dungeon construction kit, with neighbourhoods and factions and a map, and often an introductory adventure in the back.

Very few are good at the second. In most of them, the elements of the city are laid out clearly enough, but there aren’t a lot of handles for the players to grab hold of.

Recently I’ve been playing Fallen London and admiring how good it is at both of these tasks. First, it’s totally focused on the player’s actions, using their decisions to gradually open up ever-more-complex vistas onto a genuinely deep, intriguing world. Second, it really understands the particular affordances and opportunities that cities offer, which are different from those of the dungeon, the wilderness, or the sea.

Big deal, you say – it’s an interactive game, of course it handles the game aspects well. OK, but it also reminds me strongly of GURPS Goblins, my favourite city supplement of all time, which manages to take the same approach in book format.

Fallen London is a lot of fun, and free, and doesn’t require any special downloads, so I recommend you go play it, if you haven’t. GURPS Goblins is out of print but not hard to find. Don’t worry about it being GURPS – the rules bits are easy to convert and anyway, the setting and presentation are the important bits. The fantasy Dickensian Londons that both products present are slightly off the standard fantasy genre paths – the latter more Pratchett-influenced and deliberately comic. I like that about them, I think it’s part of their strength, but if you want vanilla fantasy, they still have a lot to teach you.

What they get right is that they concentrate on what the player is going to do, right now, to interact with the city’s parts. At every moment they offer the player hooks to snag their desires, opportunities to get into trouble, and longer-term goals and obstacles, so that the players generate their own adventures.

Both of them present the city as a set of hierarchies, for the players to level up through. You start in the gutter, stealing bread. Once you’ve solved the problem of starving, you start climbing a social ladder that takes in servanthood, guilds, highway robbery and positions of responsibility until at last you mingle with (and lift jewels off) high society. And here’s one of the clever bits: along the way your horizons and webs of interactions keep expanding – both games recognize that you’re going to start as a lonely murderhobo with selfish interests, looking for what you can extract and consume. But then both show you how building partnerships and networks, giving back, and exploiting the history of your prior interactions will give you power and importance, while opening up new goals and opportunities. So you start with little heists – stealing sausages from the butcher’s shop, breaking backstairs windows to swipe mops and buckets to start a chimney-cleaning business – and progress to… bigger heists, sure, but you also meet other chimney sweeps and find out that they all case rich houses for a gangster, which presents you with a choice – join and progress in the gangster’s court, or alert some potential society patron that they’re about to be robbed and rely on their gratitude.

Fallen London handles the progression through logic gates, of course. In Goblins, there’s a chapter-by-chapter structure that progresses up the hierarchy – it tells the player how best to dispose of the treasures they’ve picked up in order to unlock more complex adventures, and it gives the DM advice on how to distinguish the different levels of society. One of its smartest, clearest expressions of progress is the discussion of the PC’s lodgings – a character’s social ambitions demand a certain number of rooms, from the first flophouse dormitory to a lockable bedroom, where they can safeguard their stuff, to a suite of reception rooms and even bathing facilities, so they can entertain and rub shoulders with the quality. And income, status and expenses all go hand-in-hand, so the aspiring courtier plotting to win a baronetcy has to get out there and hustle to maintain their position, no less than the grubby urchin beggar.

So this leads me to my second point, about why (counter the assertions in Vornheim) a city is usefully not a dungeon. First, it is simultaneously the arena of play and the player characters’ home base – an ambivalent status that’s reflected in all its institutions, which protect its loyal and influential denizens while threatening its outcasts and miscreants. In the dungeon, guards are always bad news. In the city, the successful criminal avoids them or pays them off, the successful courtier uses them to help guard their secrets or harass rivals. Second, as a social environment with repeated interactions, it demands social play – fealty and tribute, gift-giving, debts and clubs and favours – which is to say it builds history for the PC, so that each new challenge becomes an opportunity to deepen and broaden their network of contacts. Third, as a socially mobile environment, it demands display. The dungeoneer can skulk unregarded in their name-level Keep on the Borderlands, nipping out occasionally to raid yet another Lich’s carefully-hidden trap-park, and store up the resultant cursed gold and invisibility neckerchiefs in their attic, but the influential townie needs to be seen maintaining their position, occupying boxes at the opera, commissioning swagger portraits, renting bears for their retainers to bait, and flirting with their betters. And, apart from En Garde!, hardly anyone has ever seriously developed a game that reflects both the advantages of preferment this sort of display can bring, and the costs of failing to keep it up.

Of course, I’m not talking about just any city, here. Maybe you can skulk in your McMansion of solitude in Cincinatti, but then you’re not really engaging in the interesting chronotope of the city-of-adventure, outlined above. For that you want some analogue of industrial revolution London or Paris (depending on whether you’re an ambitious huckster or a struggling Bohemian artist) or, if you want to get right down to the soul of the thing, late Renaissance Venice.

To the extent the city is not a dungeon, it demands different characters and skills (I’m tempted to say the single most important way games distinguish themselves is in the kinds of characters they get you to play). D&D, focused on robbing dungeons, demands robber types that fit like keys into the dungeon’s locks. Monsters afford fighting, traps afford thieving, ancient mysteries afford magic. So D&D draws on Howard’s Conan and Lieber’s Grey Mouser and Vance’s Mazirian to structure both the kinds of characters the players will play and the kinds of challenges the DM will pit against them. Fallen London and Goblins are if anything even more focused: they get you to develop PCs who are themselves interesting guides to the nature of the city and its affordances. But they draw from a different tradition of fiction, in which mountebanks and chancers take advantage of the uncertain social situations for which the early modern city was famous. Fallen London offers a wry joke about this, when you pursue a mysterious arsonist, who turns out to be just like you:

You hear of them! A series of robberies. Acquaintances in high society. Wins at the ring fights. Entanglements with surface folk. Even forays into the arts of detection. Just who is this person?

Who? I’d argue that it’s the great granddaddy of urban, socially mobile mountebanks: Giacomo Casanova.

Casanova was, by his own description, a complex and difficult character – a womanizer and seducer,* a duelist, a rake, a spy, a sometime burglar, an alchemist, a charlatan, and a quack doctor. He was exiled from his native Venice three times, and yet managed to ingratiate his way into society in every capital in Europe. In D&D terms he’d be something like a thief or a bard, but neither of those classes capture his breadth. He’s just not a D&D character. He’s also one of the prototypes for a whole tradition of urban literature, taking in rakes and Romantic poets and Zola’s demimondaines and gentleman thieves like Raffles and the Pink Panther. Fallen London models him (i.e. you) with four attributes: Watchful (for spying), Shadowy (for sneaking and thieving), Persuasive (for seducing and charlatanry), and Dangerous (for dueling and the livelier kinds of raking). Note that it does not bother to model your gross physical attributes or your intelligence: it is concerned only with those reaction surfaces that grip the challenges of its world. And Fallen London, therefore, is filled with jilted duelists and enraged constables, balconies and knotted bedsheets, spies and assassins, poorly-guarded prisons and lurid scandals, for you to fall foul of, deny, evade, and just maybe control.

To get you into this “monstrous variety” (it’s also a shameless pastiche, of course, and wears its Borges and Gogol serial numbers with pride) it needs to involve you with all the city’s competing interest groups and agendas. And that’s another way the city is unlike the dungeon.

A city is at base a collection of factions, all in symbiotic relationships with each other. It’s a big ball of twine, and if you pull on a strand, an unknown and expanding number of other strands get tugged as well. It’s a social minefield, and you need experienced guides to get you through parts of it.

You may protest that this is also true of many dungeons, but here’s the critical difference: the dungeon is fundamentally an adversarial genre of interaction. The players step into it as outsiders and they seek to loot it for what they can, and then retire to somewhere safer. Vornheim assumes you go to the countess’s ball in order to disrupt it, steal from it, poison the countess – because you’ll never really be a native among its grotesque aristos. But Fallen London ties those society figures to every other corner of its web, by having you constantly leapfrog in your progress from gutter to rooftop to gallery to lawyer’s office. So it shows you how every major figure has contacts among the criminals and dock-workers, as well as the musicians and police, and it slowly makes you, too, into a native among them. The city expands to let the players in, not as invaders but participants. It has uses for them in every corner, and it turns them into supporters of one faction or another through repeated choices.

All this works because many of the factions are actively recruiting, so the player should be able to get into several of them fairly easily. Those that aren’t – the closed-off, exclusive or shunned places – are terrified of missing out, so the more experienced, street-wise player should be able to worm their way in with some privileged information and a well-connected ally.

So, in summary, if you want to run a city campaign, my recommendations are:

1. start small and low down the social scale, with short-term activities that lead to longer-term goals, familiar to murderhobos. Then, through every one of these early adventures, introduce helper characters, who the players have to remember, who can owe them favours over time, who can be asked questions and offer hooks in future escapades.

2. make the routes to advancement obvious, but strewn with perils. Make it clear early on that you may be able to steal those diamonds but if you do, you’ll never be able to use them to get close to the Countess, which is in the end far more valuable.

3. encourage adventures that are outside the usual heists and menace-hunting expeditions – making contacts, impressing guilds, learning and exploiting personal information, romantic entanglements, no matter how mercenary they may be at their root. The players’ histories will come to represent the city for them – and will give them resources to draw on, which is to say, something to lose.

4. never introduce a faction without first thinking about how the players can use it, why they should want to get involved, and why they might care. Corollary:

5. make it clear that helping others will help the players eventually. Maybe there are resources, secrets, mysteries that the players will hear rumours of but can’t get hold of unless they can influence some certain set of people. Now they have to actually get involved in the lives of intermediaries, in order to realize their goals.

6. eventually, by all means, make it dizzying and complex. Make the players long for a map and a notebook and reminders of the hundred schemes they’ve opened up. But not all at once: introduce no more than two more elements, goals or factions per session. That’s how you get reel them in.

7. keep the barriers to entry low, but the paths to advancement twisty and arduous. Always offer ways to make lateral progress – it may be next to impossible to get into the Ninja Guild, but it’s easy to join some band of street ruffians that have members who’ve had dealings with the Ninja before, or who, it is rumoured, the Ninjas watch closely for promising newcomers.

8. and never tell them they can’t do something because of what class they are. The city is the place you can reinvent yourself, constantly, and where you can always find specialist help, provided you don’t mind forming a partnership.

* it turns out that the original author of Fallen London, like that of Vornheim, has been accused of sexual misconduct and some kind of abuse. I don’t know, I wasn’t there, I have no special reason to doubt the accusers. Allegedly he’s not involved with the game any more. Given that you play pseudo-Casanova in the game and historical Casanova was a thoroughly reprehensible abuser and child-molester, and you have the opportunity in the game to fantasize about seducing various fictional characters, that may be a kind of complicated fun that isn’t for everyone. Or maybe the fact that your character isn’t called Casanova or that Casanova lived more than 200 years ago makes it all OK, Personally, I just think the game is a fine piece of work and have no opinion about the rest.