Archive

Singing in the Wilderness: reconstructing Dune pt.3

I thought I was done, but one more thing…

The biggest of all Dune’s sinews is probably scarcity: the whole book is a paean to the power of lack. Water is scarce on Arrakis, friends and manpower are scarce for the Atreides, Spice and transport are scarce in the universe. The importance of maintaining that scarcity is why Dune doesn’t mash up all that well with many other fantasies – there are ways to do it, but they’re not easy or satisfying.

There really should be a stage play. Although I’m not sure a rock opera is the right way to go.

In contrast, Star Wars is built on abundance and therefore threatened only by willful, perverse malice. The galaxy abounds in habitable worlds, a smuggler or a fugitive Jedi can always run to one that lies forgotten, off the main trade routes.

A guerrilla rebellion can keep regrouping and recruiting endlessly, beyond the gaze of power. It also has abundant time – old religions lie buried for centuries while the worlds move on around them, fructifying in the fertile loam of resentment and once-and-future lost causes, while Dune, despite its 10,000 years of stasis, is right on the edge of collapse when we arrive.

You could force Star Wars and Dune together – if Star Wars’s galaxy, reachable by jump drive, is all shallow then the Guild’s deep reach is intergalactic or interdimensional. The connections the Guild makes are completely arbitrary and strictly limited – they could be across time or genre as well as space (and it might be fun to add a little time travel to Star Wars’s relentlessly expanding universe and to hack Dune’s prophecies and portents – a Heighliner could shuttle between the Coruscant of Darth Vader and Alderaan of a thousand years before without collapsing the Star Wars universe, as long as the Guild kept a choke-hold on who and what could take that path). But it wouldn’t add anything very dramatically interesting to the Dune side, I think, because the drama of Dune depends on restrictions on action. Work with the Emperor or become a pauper, fugitive, renegade. Work with the Guild or be exiled. Like Sartre’s No Exit and Greenaway’s The Cook, The Thief, it’s important that Dune’s players are locked together and that there is no useful outside to Dune’s political chambers.

Dune’s scarcity also breeds secrecy – the Schools jealously guard their special powers; the competitions and vendettas over resources have a desperate edge because they’re all zero-sum: there is this much and no more. So I think if you want a bit of Dune flavour but not the whole Duniverse, it might work best in a wainscoting fantasy setting – something like Harry Potter or Narnia, where the Guild and Bene Gesserit can be secret societies hiding in the plain sight of Postwar Britain, or whatever other claustrophobic setting you prefer.

for Tim Powers fans, Mark Molnar has already provided the perfect poster for mashing Dune up with Declare. Disquietingly mobile rocks might be the Sandworms of the esoteric djinn Cold War.

Am I just saying “try adding the Bene Gesserit to your Unknown Armies game”? Honestly that’s not a bad idea, but instead it occurs to me that Dune might be a great third ingredient for the Traveller-Narcos game I proposed a while ago.

In this setting, the Spice is illegal and desired nearly everywhere in the galaxy – partly for the reasons cocaine is illegal (addictive, socially disruptive, too much fun), but even more so because it’s actively dangerous to the rules that States operate by: it can offer prophetic visions of the future that collapse the stock market, it extends lifespans to the point where life insurance no longer makes sense, and it just might let you migrate invisibly to someplace the State cannot catch and tax you. Spice smuggling is in the slippery hands of giant, vicious cartels and is such a big business that it inevitably destabilizes any individual planetary government it touches. Most ordinary criminals won’t touch it for fear of the cartels’ weirdo assassins and trackers – which include some cult of mind-reading women and a shadowy “guild,” that isn’t in any one cartel, but everyone seems to be afraid of. None of the Trade is carried on computer media – too traceable – but instead rests encoded in the heads of the cartels’ Mentats – and the various cadres of undercover cop Mentats, the product of training programs by governments that have invested a Spice-price in trying to stuff the genie back in the snuffbox. You play a smuggler cell that might unwittingly be a deep-cover government operation, trying to pay off your crippling ship mortgage by doing covert missions for a mysterious handler, which keep pulling you closer and closer into the secret heart of spice production – some backwater desert planet infested by murderous vermin.

When you finally make contact with some actual Spice producers, it turns out they’re nothing like the zero-sum desperadoes in transport and distribution. In fact, they seem completely uninterested in making any money off the stuff – long-term, high-intensity contact with Spice has opened their minds to the point where they no longer experience scarcity at all. They can offer you direct transport, ship-free, to the multiverse – a world of perfect freedom in which all the power structures of your own world would collapse, for lack of handles on the populace.

On a throne of an apartment

With a wide open

Mouth full of teeth

Waiting for the arrival of death

Because far from the

Flagged fences

Which separate yards

On the calm peak

Of my eyes I see

The soft sound shade

Of a flying saucer

So the question is, do you go with them on an adventure where you don’t need money, or do you take the trappings of scarcity’s upper crust?

these guys insist all you need for this adventure is a book of verse, a jug of wine, a loaf of bread… and enough hyperdrugs to swim in. Also they have a busted old Airstream caravan and some ugly macrame blankets covered in cat hair.

Art by Mikhail Borulko.

ˇ

ˇ

ˇ

(Because the funny thing about Herbert’s magic mushroom universe is, it’s so damn Capitalist. Right in the middle of the postwar freak-out, surrounded by the hippie promise that all this Square materialist fear was just a crisis of the birth of the New Age, there’s Herbert the anti-hippie in goddamn Oregon tripping on dreams of endless and inevitable slavery and doomed Mohammeds and tragic millenia, cranking that old Wheel of deceit and violence around One More Time.)

“And do you think that unto such as you

A maggot-minded, starved, fanatic crew

God gave a secret, and denied it me?

Well, well—what matters it? Believe that, too!”

― Omar The Tent-seller, Quatrains

Machines As The Measure Of Men: reconstructing Dune pt. 2

(part 1 discussed Dune’s factions and drew a distinction between those parts of a setting that make it work (the sinews) and those parts that are pure flavour, that could be reskinned without risking the setting falling apart or becoming incoherent (the fat, maybe). I recommend reading it before this part.)

2: Technologies

Villeneuve’s best work in Dune is in getting machines to tell the story. Every machine has the personality of the people who made it. Each one reinforces its maker’s power position in the narrative.

First, all the stuff that comes from off-world is a study in scale contrasts. The brutalist carryall from Lynch’s Dune is now the basic spaceship form – they still hang in the sky like bricks don’t but under Villeneuve’s carefully-angled cinematography they’re beefed up the point where you wonder why the Atreides ever disembark from them – they could just flatten Arrakeen and replace it.

As for making the factions as distinctive as possible, Villeneuve’s approach is (sometimes) radical. The Harkonnens are rather unimpressive on Arrakis – black-clad, pallid, fat goths – until you realise their home world is literally black and white or, rather, infra red, like their thinking.

And while the Atreides and Harkonnens fly brick dumpsters, the Emperor flits in on Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate – an effete, feckless look for an ineffective figurehead.

But the masterpiece of the whole film is the Harkonnens’ spice harvester. Villeneuve sets us up for meh with the basic harvester in part 1. It’s big but… flat, like NASA’s Crawler Transporter. It’s what you’d expect a harvester to be – a supporting player, not poised to steal the show from the charismatic lead.

But that, you see, is a jank old busted harvester, what the Harkonnens leave behind for the Atreides to complain about. The real Harkonnen spice harvesters, when they’re finally properly unveiled in part 2, are a symphony of signs: colossal, overweening, top-heavy, parasitic – like the spider-head in John Carpenter’s The Thing.

And of course it’s all ironic: the bigger they are, the harder they fall to a bunch of Fremen who pop up out of the sand exactly like the anti-tank miners in Stalingrad.

Because one of Herbert’s big sinewy ideas is: comfort makes you weak. Getting a machine to do your work is inviting disaster, because someone who is tougher (because he doesn’t have a machine) will take everything from you. Or, as Mad Magazine put it in 1960:

BTW for a really good discussion of technology, power, and their attendant colonialist superiority complexes, check out Michael Adas’s book, which supplies this post’s title. I think Herbert was suspicious of technosaviour arguments, as Adas notes the British and French were, just in time for Vietnam. Whether his Fremen were secretly based off the Viet Cong, Iranian Revolutionaries or any other IRL group is beyond the scope of this blogpost.

Anyway. Herbert’s second sinew is less often remarked: being tougher doesn’t make you politically smarter. The Fremen and Sardaukar warriors are technologies, too – conditioned by neglect to be “tough, strong, ferocious men,” they are also therefore vulnerable to the old mind tricks: “play on the certain knowledge of their superiority, the mystique of secret covenant, the esprit of shared suffering.” Get that right and they’ll be strongly, ferociously, fanatically loyal and obedient. Although once you’ve set them in motion, they’re also liable to be as hard to stop or redirect as a Harkonnen spice harvester. Once they’ve got an idea in their heads, it’s almost impossible to dislodge it with a new one.

Cue another Dune sinew: the Superior Man is flexible. He makes use of tools but is aware of how those tools will try to shape him. He refuses to be shaped except by his own will.

(Does this sound like Mein Kampf? Noooo, it’s probably just Nietzsche.)

The most thoroughly iterated representation of this idea is the Holtzman shield generator.

Shields are wonderful at keeping you safe except for when –

– the enemy has clever slow-bullet guns that pause politely at the shield’s edge to tunnel inexorably in, like something out of an Edgar Allen Poe story;

– the enemy has lasers, because when a laser hits a shield you get an atomic-style explosion;

– you’re out in Arrakis’s Wild Manhood Testing Country, where they attract frenzied worm attacks;

– you can’t use your shield and you have to knife-fight anyway, in which case your “slow on attack” training gets in your way.

…still, everyone uses them all the time. You can see who is the master of their technology and who is mastered by it by how they behave when the technology doesn’t.

See also the Imperial doctors’ Pyretic Conscience (which doesn’t work), the Guild’s precognition (spoofable by Tleilaxu, but then so is everything), Hawat’s security searches for assassins (didn’t look in the cupboard) etc etc.

Aside from generating dramatic tension and highlighting the fallibility of the best-laid plans (a fallibility that is necessary to the whole Fremen uprising plot) this is a classic game design principle: if you add something super strong, give it an Achilles heel.

What can we do with this? Well most of all, think of weaknesses for all the major Classes (BG, Mentat, Swordmaster, Doctor) that brings them back in line with the Sardaukar and Harkonnnens. The classic Dune move is to make people too confident in their strengths. But a Bene Gesserit can’t mind-read a typed note or an ignorant emissary (Doctor Yueh deliberately clouds the Bene Gesserit Jessica’s observations by manufacturing an embarrassing situation), a Mentat can quickly get lost in paranoid mirror-mazes, Swordmasters rely on faster-than-thought training that can be exploited

and Doctors… well, they care too much. Similarly the fastest ornithopter shouldn’t be the most maneuverable, the biggest worm shouldn’t be the most tractable etc.

Maybe the biggest sinew, though, is to replace machines with people. The Mentat as human computer has already been mentioned, but the motif is everywhere. Why have a scripture when you can have oral traditions? Why a recording device when it could be a person with eidetic memory? Conceivably, you could replace weapons, horses, cars and telephones with talented humans. I would say furniture, but that’s a bit too Book 5 for this post. Or mix the functions up: a Bene Gesserit is in many ways a social Mentat – their skills at manipulation, cold reading, and masking their own signals make them a technology of persuasion. Someone who was able to open doors into gatherings could be social harvester, someone who can keep things secret might be an information swordmaster. I dunno, maybe this is all too JoJo but Dune has so many little superpowers, lightly explained that I think you could really go wild with inventing new ones.

3: Space Splice

While we’re on the topic of replacing machines with people, have you ever noticed that the spaceship computers in Classic Traveller are generally the size of a stateroom? You could easily replace them with the living quarters for a Mentat (Wizard of Oz curtain optional), with bigger ships requiring higher-status mentats who demand more palatial accommodations, according to strict sumptuary laws.

Herbert does not explain how the Guild achieves interstellar travel…. until Book 5, which came out a year after Lynch’s movie, and which gives the same explanation Lynch gives: the Guild Navigators “fold space,” using their esoteric mind visions. So that’s neat: the Jump Drive is also a person, with bulky quarters full of spice gas. Dune’s Guild has a monopoly on interstellar travel, though, so there would be no jump drives except for the gigantic Guild Heighliners.

It is curious, though, that Herbert doesn’t explain how interstellar travel works until Book 5, 20 years into writing the novels, because:

1. everyone else who writes an interstellar empire epic in the 20th century offers an explanation for how it’s supposed to work – Jump drives or Hyperspace or Warp or interdimensional gates or corridors. Everyone has their own way of kowtowing to Einstein’s assertion that you can’t go faster than light, and then saying “here’s how we’re ignoring it.”

2. the rest of Dune is so damn didactic. It’s the perfect book for high school analysis essays because you can say “Herbert thinks struggle makes you stronger because he says so, first on page 26 through the mouth of Leto, then on page 27 directly via the omniscient narrator.”

But when it comes to how the empire is tied together, what the Guild’s all-important monopoly rests on… nothing. Except that Guild Navigators needed Spice to “see a safe path” – because if you’re going really fast, you don’t want to run into any pebbles. Or hydrogen.

So… maybe this is overreaching (although if anyone ever invited a Talmudic/Koranic exegesis of their novels, it’s Frank Herbert) but… what if Herbert kept quiet about this not because he himself was ignorant or uninterested in the Einsteinian problem but because he wanted to maintain the mystique of the Guild? No-one outside the Guild knows how the Guild does it. More than that, what if the point was, nobody in the Duniverse knows FTL travel might be a problem because they don’t have the scientific background? In Dune’s lore, the 5 great schools of knowledge (Swords, Doctors, Mentats, Bene Gesserit, Guild) are set up after the Butlerian Jihad, which was fought against computer AIs. Developing computers requires Einstein, quantum mechanics, and higher math. So… the schools restrict access to science and (to be safe) calculus. The rest of Dune is socially… what? 16th century? In our own history it takes about 300 years to get from there to Einstein. How would you prevent that development for 10,000 years? By funneling everyone into very deliberately constructed educational pathways and teaching them curricula that neatly sidestep the required questions, then giving the guardians of various fields of knowledge social positions they want to defend, that come with neatly circumscribed professional formations. Herbert is obsessed with mental and social conditioning and he specifically mentions that doctors and mentats have trained restrictions. The other hint here is that the Great Houses’ “family atomics” are all supposed to be 10,000 years old – irreplaceable relics of the Jihad (and Dune was written at a time when the discourse of nukes was that they lasted forever). So: only the Guild school is entrusted with relativity. …and, probably, with Maxwell’s equations for electricity and light, which were what set Einstein off in the first place. And only the Ixians and Tleilaxu disobey the restriction and they keep very quiet about it for their own mnopolistic reasons.

All that said, fundamentally, the situation offered is actually quite familiar for gamers:

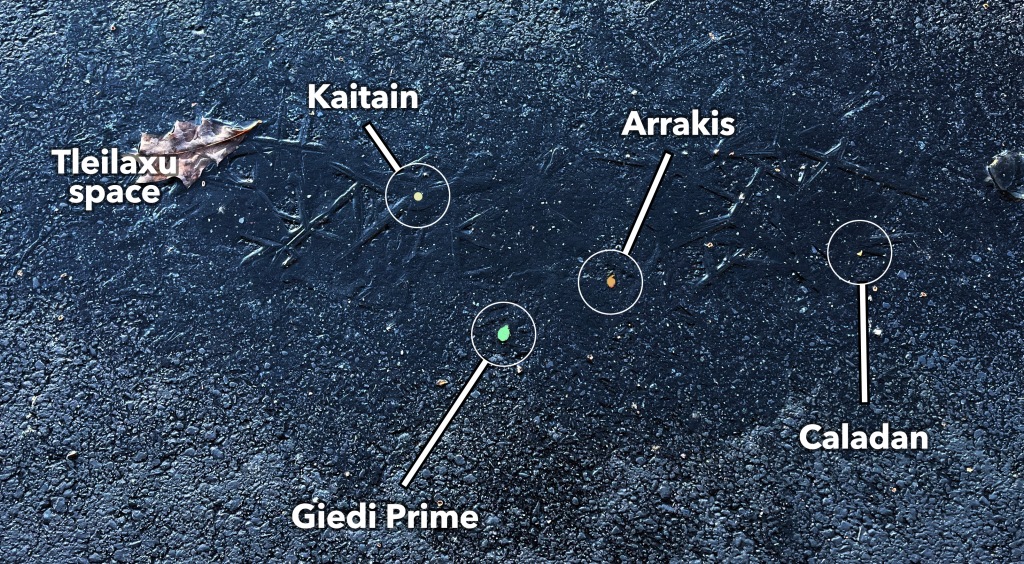

Travel within a star system is “shallow water” – anyone with a simple spaceworthy craft can do it (Houses, smugglers, assassins etc). Going from one star system to another is “deep water” and requires a Guild Heighliner.

I say that, but I can’t actually remember Dune ever taking advantage of multiple points of interest in a single system (in the book it seems that the Guild actually restricts Houses’ rights to fly their own ships around, which makes me wonder how much of a capital drain a space warship is on a House that can hardly ever use it). Which is too bad, because star systems could get really diverse: “shallow” could be a busy star system with twelve warring planets, or several moons around a single gas giant, or a lively asteroid field for mining. It could also be an enormous nebula, a couple of light years wide, populated with enough gas and little rocks and radiation and brown dwarfs to keep tramp ships powered and occupied for decades. (Nebulae could even be no-go zones for the Guild’s big hazard-averse ships).

(BTW the shallow/deep divide in Civ has no physical justification except that “shallow” might mean “easily accessible to an unidentified harbour of retreat,” so in theory unstable ships like galleys could run to shelter from storms from the “shallows” but would be forced to ride those storms out in the “deeps.” but don’t let that worry you, it’s a wonderful bit of game design anyway to be able to see the excitement over there but then have to devise an ingenious method for getting to it.)

There are many ways to set a shallow/deep division up – maybe you need a special ship or map, or only a native guide can get you across the deep desert, or only a government cyberdeck can get you into the government’s servers… the point is you have to work with the Church to get into its Treasury. Imagine Han Solo in this situation: he can smuggle all around the solar system but if he wants to get from Tatooine to Alderaan, he needs to forge papers or bribe an official, get on a Heighliner and “fly casual” right under the nose of the Grand Moffs who are coming back from obliterating Alderaan a moment before. Because also people can see who else is on a Heighliner but they can’t do anything about it without endangering their travel privileges. Imagine the Guild letting people off at a system that no longer has a trading planet, or being evasive and dropping them at the wrong destination. A Death Star could only exist if the Guild were complicit in the Emperor’s planet-busting reign of terror or if a rogue splinter-Guild drove it around, causing a crisis in everyone’s confidence in Guild neutrality/ethics/reliability/violence.

4. Dune, Ripple, Wave

Finally, I guess I’ve already tipped my hand to this one but of course, Dune’s shallow/deep structure, like everything else about Dune, could work at any scale.

The stated scale – galactic spread, billions of unmentioned subjects – presents all sorts of problems (that Herbert doesn’t address), but an ocean or a big sky full of Flash Gordon flying islands or whatever could give you the same fun. Shallow could be estuaries, archipelagos, reefs, tower blocks, subway stations, university departments – any space that’s somehow bounded, where connecting to another such space offers a different challenge from getting around the current one. The point is that if you get the sinews right, you could reskin and rescale Dune in all sorts of ways to fit your home gaming group and still get a recognizably Duney campaign.

What if you reskinned Dune just lightly, to play up the early modern exploration vibe and play down the (clearly uncomfortable) sciencey part of the fiction?

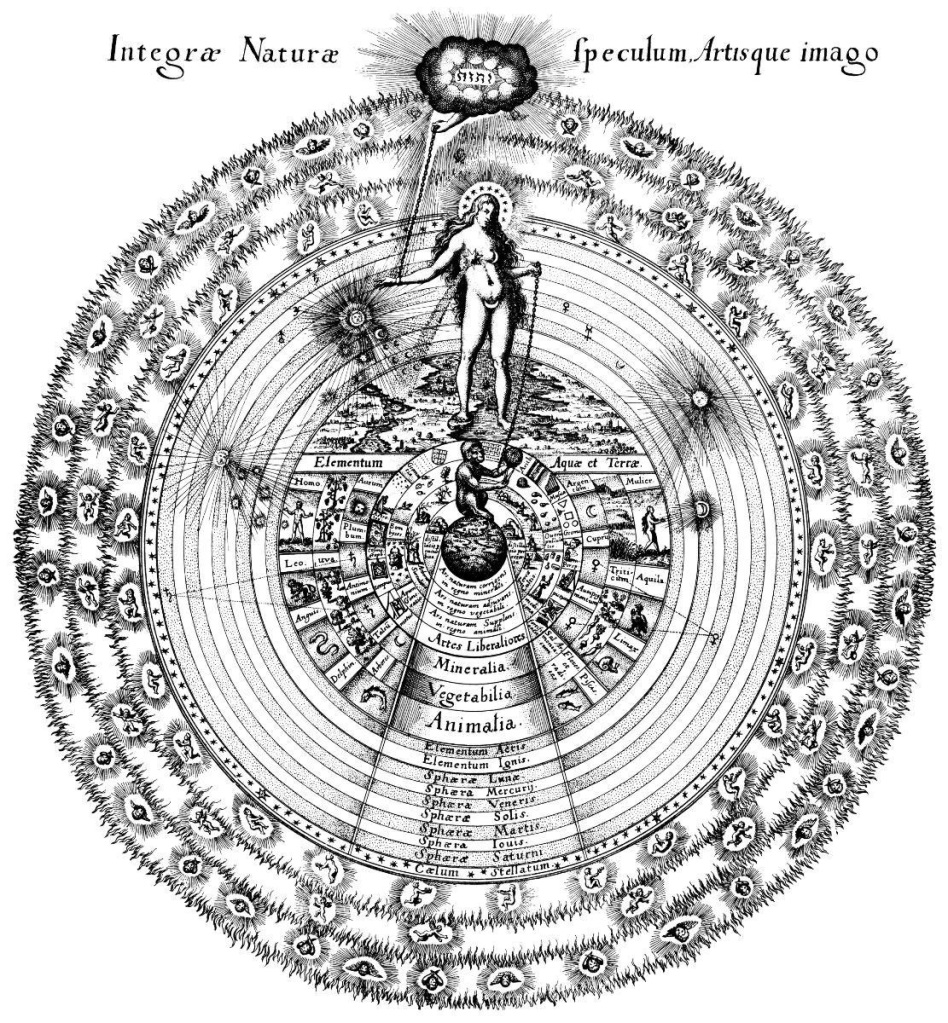

It is the long 16th century – somewhere between 1480 and 1648 – and everything and everyone you find in that span is fair game. The Emperor, Charles-Philip of Spain, is bent on spreading his rule across all the unknown realms of the universe – both those across the seas and those of Angels and Devils. He has become so powerful that he threatens the unity of the Holy Mother Guild and it is rumoured some Cardinal Navigators have promised to open up their routes for him, to the Outer Spheres, where the Angelic Guild Superiors keep their fruitful kingdoms and permanent warehouses.

Only a coalition of the Great Houses (Tudor, Valois-Angoulême, Ottoman, Syah, the Bohemian and Austrian Habsburgs, etc) can stop him, and then only if they can keep him from discovering the sources of Radiant Spice, for which the Guild thirsts. Rumours abound of Spice sources across the seas:

– fountains of youth,

– cities of Brass and Djinn,

– Ambergris floating on the foam,

– islands made from a single nutmeg, from which all other nutmegs grow,

…and of Other Worlds offering trade and conquest:

– El Dorado,

– Far Cathay,

– Agartha,

– Hy-Brazil,

– St. Brendan’s Isle

– the paradisical Isle of Pines.

Any of them could seduce the Guild to the Emperor’s path, all of them are said to offer a way to the fabled Prime Mover and a Great Synthesis – if Charles-Philip could reach that, he would become sole and eternal Emperor of all.

The Mentats John Dee and Ignatius of Loyola translate the secret languages of the Angel Guild for their respective rulers. Giordano Bruno, kept captive in the Guild Embassy in Rome, charts the empire-to-be in his Memory Palace.

The Bene Gesserit are a secret sisterhood of basically every woman you’ve heard of from the period – it is rumoured that all women are members, whether they know it or not, especially all the wives, mistresses and wetnurses of royalty. Known Reverend Mothers include Isabella of Castille (the Emperor’s long-lived grandmother), Elizabeth and Mary Tudor, Artemisia Gentilleschi, Aphra Behn… and the Missionaria Protectiva are said to have been active among the Amazons of Benin and the Wonhwa of Joseon.

This proto-Dune hovers on the brink of the long-term stability that Herbert’s book tears down: the Spice monopoly is still out in the rumoured wilderness and up for grabs. The most vicious fights are over speculation – about where the Spice might be, about what it might unlock. The Guild still controls access to eternal life, though, and nobody (yet) dares to openly defy it, even as they try to tease its members away into supportive splinter sects.

next: Post 3: Dune Mashups

Wind, Sand and Stars: reconstructing Dune pt. 1

Villeneuve’s Dune follows the dictum “art is deletion.” The director loves nearly-flat textures and deep bass drones and minimalism and brutalism and the Bene Gesserit

and deletes much of the rest – the Guild, Mentats, Herbert’s eccentric approach to scifi, computers, and space travel, the Duniverse’s long, repetitive history of Jihad.

Bravo. A strong editorial hand is simply necessary for making a film out of Herbert’s sprawling, invention-filled novels. You can’t make a Dune film without breaking ergs.

But that leaves a lot of potential Dunes on the cutting-room floor. So this post and the one after it are about other choices you could make to construct a campaign out of Dune’s ingredients.

Also, I have a sense that some players are reluctant to engage with Dune, either because they think they need to learn a wall of lore or because they don’t find it inhabitable. Han Solo opened up a giant door into Star Wars – you didn’t need to be an Important Person, you didn’t need a ready-made destiny plot, you could just be smuggling around the galaxy, fixing your jump drive with a kick, shooting scaly anteaters in dive bars. My hope is that these posts might open up some doors into what Dune has to offer – how you could play as someone other than Paul. In terms of scope, I too am afraid of the wall of lore that Dune develops in its later volumes. I restrict myself to the first 2 books, the bit covered by Villeneuve’s trilogy.

The title of this post, BTW, is stolen from Saint-Exupéry’s memoir of delirious revelations he had concerning the state of humanity, machines, and God while stumbling away from a plane crash in the Sahara. He fell from the sky and was rescued by Bedouin and felt himself stripped of everything but his humanity and maybe some wisps of divine protection.

I highly recommend it as fuel for a dream-logic Dune, connected by spore-tendrils to Frank Herbert’s blue-tinged musings on consciousness-expansion.

The Ingredients

Film schools tend to teach that stories are made out of characters, plot and setting, in that priority order. Get the characters right, you’re fine. Have them do some plot while you’re learning who they are. Nice. The setting is tertiary and basically interchangeable.

I think that’s why SF and fantasy movies so often come out wrong – they put setting at the bottom of the pile, when setting is the reason why a story is SF or fantasy. What if, instead, we think about stories having a heart (the reason the story exists), a skeleton (structure, often borrowed), and sinews – the parts that mobilize the narrative, that drive it along, provide reasons and resolutions. Those sinews are often lumped in with setting but they’re not the same: setting is kinda akin to fluff, sinews to crunch. You might be able to reskin a setting, but only if you get the sinews right, because they make it work. The ingredients I’m interested in are the sinews.

But let’s get the heart out of the way first. Dune is, like Star Wars, mostly a pastiche, and superficially the two look identical: little guys against a big empire (a familiar theme around here).* Original Star Wars’s heart is Kurosawa Samurai epics plus Dambusters or, to put it another way, “honor and daring ingenuity can beat any giant structure.” People talk about SW being good vs evil but the goodness of the heroes (and even the specialness of Jedi), especially in the first outing, is secondary to their quality of daring, of defying the odds and doing it anyway. Dune’s heart is Lawrence of Arabia:** “every triumph contains the seed of its own destruction.” And the more absolutely you start out as the hero, the more certain you are to become an agent of villainy. In Lawrence it’s super explicit: his success before the intermission is punished after it. And retrospectively you can see his failure was always there, waiting to be expressed. Dune makes it explicit by having characters who can see the future, so it doesn’t have to be retrospective: Paul, the Bene Gesserit, and various others can see the tragic arc, the rot in the bud, at every moment. They can sense the destination but they take the journey anyway.

* obviously I’m only talking about the first Dune book and the first SW movie here… well, maybe the first SW trilogy. We do not speak of anything above the number 3, ever.

** I mean only the movie Lawrence of Arabia, which is different in many ways from the memoir from which it draws. Movie Lawrence’s heart is partly borrowed from Kipling’s The Man Who Would Be King. And the movie of that is also a very good companion piece for all of this. It should clear up any confusion about whether Paul’s a straightforward White Saviour (he isn’t).

Also yes I know, both Lawrence and The Sabres of Paradise are cited as literary inspirations for Dune. When I’ve read Sabres I’ll get back to you about what its heart is.

But Dune is not only that Big Theme, it’s also things revealed to Herbert by magic mushrooms (Jungian things about the wise power of women; eccentric things about how gay men are destined to go into the army). They’re a grab-bag but for Herbert they’re all Deep Truths. Mankind as a species is threatened by stagnation. An unexamined life is not worth living. Machines and comfort are counter-evolutionary. Nothing boosts growth like death. Nietzschean type stuff, mostly. And those things are what the sinews express.

1: Factions

Instead of Star Wars’s unitary Evil Empire, Dune offers a giant cage match of multiple, cross-cutting power interests with specialized realms of control and unique abilities, like highland Sri Lanka or the video game Hero’s Hour. Here’s the special thing Dune brings to this: even though they have different aims and they play on different chessboards, these factions can only make temporary alliances because they’re working towards philosophical/eschatological end-games, that only they really understand. Each one believes they must be in control, and soon, before the next apocalypse. Everyone has heard about the last apocalypse 10,000 years ago and is sure another one is just around the corner. When it comes, all mankind will be glad that they, faction (X), are in control.

The most familiar chessboard contains the Great Houses and the Emperor who are pretty much the Holy Roman Empire but spread over a galaxy. Compare them with Game of Thrones: the Houses compete in marriage, diplomacy and war. They have special strengths and weaknesses (and you can make more up at will). The visible parts of their courts are also the same size as GoT’s Houses – a nuclear family, a few servants, an advisor. Dune’s Houses are distinctive in also having hereditary bureaucratic functions, so imagine, say, the Harkonnens as the Bushes, with ancestral control over the CIA, and the Atreides as the Kennedys, born to run the State Department. Or the Tafts as the IRS dynasty. Houses could have any weird eschatology you can dream up but they’re mostly all worried that the Emperor isn’t doing a good job of staving off the apocalypse, so he must be replaced. Coincidentally becoming emperor would allow a House to pay off its enormous debts to over-mighty bankers from the Imperial coffers.

Dune’s special sauce here, which changes everything, is that the Houses and Emperor are in a political tripod with CHOAM – the honorable company that holds a monopoly on all interstellar trade and which controls (like OPEC) the flow of Spice. (the full name, Combine Honnete Ober Advancer Mercantiles, means exactly the previous sentence) Real power (and unlimited money) comes from a directorship in CHOAM. CHOAM locks the Houses together: no matter how many of your children they’ve killed, you still have to cooperate with the other CHOAM directors, or nobody gets profits. And CHOAM depends on (is really an arm of) The Guild, which has a (near?) monopoly on interstellar transport. (CHOAM also incidentally recasts all the Houses as colonists of their homeworlds rather than feudal fiefholders – they’re concerned with cash crops for the external market).

Of course the Guild keeps its closest eye on the Emperor, who can dispense great gifts (like contracts for Arrakis) but can’t hold onto them, making him maybe more of a Trobriand Island chieftain than a Habsburg or a Roman-style emperor.

Being Emperor is like being a noble but more so: first among equals, he has no friends. There’s no step up, only down. And his Sardaukar legions are like Varangian guards or the Caliph’s mamluks – they’re the world’s strongest army so they’re well placed to seize power themselves.

The Guild controls all interstellar transport and has its own bureaucracy, training school, religion, and god knows what else. It’s ruled by Guild Navigators, who can see the future and don’t like it. They know they’ll never be more profitable than they are right now, and right now their profits depend on their transport monopoly, which in turn depends on:

(a) a technological edge – giant interstellar-capable ships;

(b) Spice – a drug that lets you travel safely between stars if you get high enough and have spent centuries turning yourself into a Guild Navigator.

If anyone else replicates these technologies, the Guild’s profits will plummet and it will lose its stranglehold (through CHOAM) on money and politics.

So the Guild spies on everyone to make sure they’re not developing transport or spice-like technologies, and tries to maintain stability while knowing that there’s nothing harder than preventing change on a big historical scale.

Things that makes the Guild interesting as a faction:

– better spying via mysterious future-sight, which is largely “seeing probable outcomes.”

– unmatched mobility and secrecy – the Guild knows whom it has transported and to where, but nobody else knows where the Guild’s ships are. They could be servicing a whole other Empire for all the nobles know. There are hints that they service some planetary systems that aren’t part of the Empire but are… in hiding? In wait? Supplying secret goods?

– truly unpredictable political alliances. They alone don’t want to be Emperor instead of the Emperor. Maybe they want to replace the Emperor with a more secure or weaker one but only to keep the Houses out of their business.

– highly predictable triggers: they don’t want innovation, especially in spaceship technologies. They want to control every gram of Spice. They don’t want anyone to know things they don’t know.

But…

– they’re total unable to hide their nature. Their top ranks have mutated (gotta say I like Lynch’s interpretation, which looks utterly inhuman) so they have to do any spy work through intermediaries.

– they’re totally dependent on huffing enormous, expensive vats of Spice, which have to be continually replenished. The Spice must flow because without it (a) there is no space empire, but also (b) the Guild will come down off their millenia-long high like lizards falling off Balinese palace walls.

The political tripod has some interesting effects on war and diplomacy. Outright war between Houses requires armies to be transported by the Guild, and nobody can afford to be cut off by the Guild, so any war-fighting has to be negotiated with them first – you don’t want your invasion force to be denied a ride back home. The Guild is “strictly neutral” but even more strictly in favour of long-term stability (which might involve removing you, troublesome Duke!). So you tend to get limited wars – mostly of spies and assassins, mostly leading to situations the Guild considers more stable. That’s one reason why CHOAM directorships are the real Victory Points – you don’t have to transport them.

So playing a noble or seneschal of a House really offers three modes, that you can slip between for different situations.

- Out in the provinces, where the Guild doesn’t care so much what you do, it’s like Game of Thrones: each House stands atop ornery, maybe rebellious subjects, and other Houses’ assassins could blame a noble’s death on their own local troubles. Spying on what other Houses are doing is a survival tactic. Being able to report anything improper to the Emperor or Guild is a bargaining chip.

- In formal settings, like the Emperor’s Court, you’re under the full glare of Diplomacy but you’re also doing all the business of Dynasty, so think of the betrayals and ridicules of Versailles, the intrigues of Richelieu, hurried missions for Musketeers that have to be completed before the next public Ball. Outright assassination at the Imperial Court is liable to spook the Guild but making others look like bad partners/marriage prospects is exactly what it’s all about.

- CHOAM meetings are about trade negotiations and shipping contracts, which means doing favours for Guild ministers and competing to sell your goods across the Galaxy in preference to the goods of other Houses. Interstellar shipping is very expensive, so those goods will all be either great luxuries or special innovations your finest engineers have dreamed up… as long as they don’t stray anywhere near long-haul spaceship tech or computing (more on that below). Most of all, though, CHOAM meetings are about getting access to Spice. The Guild is the biggest customer, but everyone wants Spice because it extends life. So obviously the Dukes and Barons want it but it’s also the best thing in the world for keeping their advisors, administrators and army chiefs loyal. Assassinations at CHOAM meetings seem like a very bad idea, and social standing/reputation probably doesn’t matter so much to the hard-nosed Guild, but there’s still plenty of room for soft power: Guildsmen are still men, and the bigger an institution is, the more you can hide in its folds. The more human-looking Guild administrators probably chafe at the glass ceiling imposed by the Navigators. Within the Guild, the right to Navigate might be a system of dead men’s shoes, and nobody is better placed for smuggling than a Guild representative. If, in fact, the Guild is based at all on the East India Companies, then smuggling might take up more than half its shipping capacity.

Mentats are what Dune has instead of computers, and I think dramatically they’re way better: why have a mute, reliable machine holding your information when it could be a self-interested human? Whether they’re venal, corrupt, and blackmailable or idealistic, credulous, and biased, a Mentat offers so many more handles for a DM when imparting information to players.

of course, where you have continuous wars of assassins, you want your assassins and security under a Macchiavelli-style Mentat and, as usual, to complicate things, Herbert has them all train at the same school, making them a faction as well as a technology (next post).

That means they tend to know each other and have their own agendas and jealousies – the Harkonnens’ Mentat deliberately trolls his Atreides counterpart – partly to keep him distracted, partly for personal amusement. In theory, Mentats are supposed to be inherently ethical in their advice, but watch out! Herbert says there are also twisted Mentats, who aren’t. This is as close as Dune gets to a light side/dark side schism. Note that even “ethical” Mentats deploy assassins.

Factionally (and reasonably) they all distrust and work semi-collectively against the Guild and the Bene Gesserit, recognizing that both are up to stuff they don’t want anyone else to guess at. The Guild always wants to puppet the Houses; the Mentats are the Houses’ counter-measures. The Bene Gesserit puppet everyone anyway.

I’d recommend using a House’s Mentat as the PCs’ first patron: the players can ask the Mentat anything and get one of 3 replies:

– here’s the information

– you’re not cleared for that

– that’s not knowable/you can reasonably expect that hardly anyone knows the answer.

Because Mentats know what’s going on and are always full of schemes, they’re the ideal mission-givers and heist organizers. And then the PCs find out in mid-heist that their Mentat’s understanding of the situation was not quite as perfect as it seemed.

Mentats also have handles for the players – they’re addicted to expensive Sapho juice (no really), which they use to sharpen their minds, and often also to Spice, since long experience is a great strength for their role. They typically work alone and it seems like a lonely position: they’re never anyone’s social equal, they’re always the smartest person in the room but never the decision-maker, and they’re professional paranoiacs, seeing openings for assassins everywhere. No wonder they are so often prey to all kinds of weird vices.

It’s probably best to work up to playing a Mentat – they’re very high level – but in terms of replicating their published powers, just give the player a calculator and an encyclopedia – or the right to make up background detail at will.

If the Great Houses are the Holy Roman Empire, the Bene Gesserit must be… eugenicist Jesuit nuns? They redefine bodily control, inflict pain in the name of restraint, and are freakishly concerned with who is having sex with whom, which all sounds a bit like someone went to Catholic school. They also spread propaganda in the guise of religious revelations, presumably aided by their trained ability to see whether people believe them or are excited by what they say.

“The Reverend Mother must combine the seductive wiles of a courtesan with the untouchable majesty of a virgin goddess, holding these attributes in tension so long as the powers of her youth endure. For when youth and beauty have gone, she will find that the place-between, once occupied by tension, has become a wellspring of cunning and resourcefulness.” – Dune

Ahem. So they’re maiden/whores until they become wily old crones. Right. I swear, Robert Graves haunts this book. They learn all this stuff in their own Great School, which seems to be a totally sealed institution: it just quietly sends forth Black Widows at odd moments and people only notice afterwards. And it seems like it sends them wherever there are people to manipulate – there are apparently several high-ranked BG reverend mothers hanging out among the Fremen, whom nobody else courts. I think we can assume they’re also witching it up in all kinds of other little ignored power islands across the Galaxy, far from the Imperial gaze.

In all the visual media they’re shown wearing strange uniforms but in the book you know a Bene Gesserit by her perfect control, measured heartbeat and occasional irresistible commands. Their eschatology is the clearest: somehow they can see the future because somehow they can access racial memories but only women’s memories and therefore not enough. So they want to selectively breed a male Bene Gesserit who will be able to see the future perfectly… and then rule the universe through him. Their end-game philosopher-emperor will have the powers of a Bene Gesserit Reverend Mother (detect lies), a Guild Navigator (future sight) and a Mentat (human computer) and will submit to the control of their own admittedly less-perfect and less-far-seeing leadership. I dunno, I can’t see the future but I think I can see a potential problem with that.

If the Bene Gesserit actually won, they would be no fun at all. But until they do, they’re frantically busy seducing nobles, stealing children, ruling from behind thrones, upsetting everyone else’s plans, and sacrificing themselves and others for secret purposes that might not mature for generations. Which is everything you could ask from a villain or an unreliable ally. At the very least, the threat of interrogation by a Bene Gesserit Truthsayer deliciously complicates any underhanded mission the PCs might have been given by their Mentat patron.

There are also Great Schools for Doctors (medics but also general researchers) and Swordmasters, so there’s your Kung Fu hero. Herbert doesn’t seem very interested in their factional possibilities and has doctors subject to intense conditioning, making them feel unspeakable pain if they’re in danger of breaching their Hippocratic Oath.

So what can we do with all this? How would we swipe it for our games or make the Duniverse more legible for our players? I note in passing that the Great Schools seem to pump out very D&D-like Classes of alumni: Swordmaster = fighter, Doctor = the medical functions of the cleric but Bene Gesserit can command/turn enemies and detect lies. The Mentat seems an obvious analogue for the Int-based wizard but their spells are all of divination. Thieves/assassins are strangely absent from the basic Class roster, but maybe that means everyone has those skills, or maybe just nobles do.

There are several key points to learn from Dune’s factions for court intrigue games:

- Every time you do something, at least 3 factions are involved. If you assassinate a prince or steal a baby or bribe a trusted lackey, the affected House and their Mentat will be interested, obviously, but also there will be Bene Gesserit links because you don’t get to be noble if you’re not breeding material, and the Guild will be worried lest you trouble the status quo. At the same time, if they can, the Mentat, Bene Gesserit and Guild might present themselves as complicating allies, if they think you could serve their interests as well.

- interlocking interests make plots and the Guild + Houses is an infinite plot generator. This is essentially what Vincent Baker says in Apocalypse World with his PC-NPC triangles: if you have 2 NPCs they will have overlapping or conflicting interests, so if one asks you do something, the other will object or want a piece of it for themselves or something. Complexity = conflict = drama. But Dune actually makes that easier by having a stable NPC entity you need to consider every time, so it’s not “I didn’t know Jo wanted this necklace too!” it’s “that princeling has a Bene Gesserit mother. Her whole Order is trying to control this family and they will come down on us if we aren’t careful.”

- Which is to say: familiar pieces help you play chess. You don’t know what the Bene Gesserit want with this prince in particular, but you know broadly what sorts of things they’re concerned with: marriages, alliances, Truth-detection, pregnancies. Likewise the Guild: balance the Houses to keep them all weak, no obstacles to the Guild’s own operations, no new machines. If you’ve spent time introducing characters, keep reusing the same people. Politics is personal; if your players know the Guild ambassador is having to restrain his anger because of what they did last session, you’re winning as a DM. On the other hand, Dune’s institutions allow you replace individuals to great effect. So you killed the last Guild dude? Here’s a new one and he wants to know what happened to his predecessor and why. Remember also that everyone has trouble controlling their people – maybe the dead Bene Gesserit agent overstretched herself? Maybe she was on a secret mission the replacement doesn’t know about? The replacement will not automatically be an enemy.

- Even though Herbert keeps saying “ohohoho plans within plans,” actually much of what happens is improvised and paranoid knee-jerk reaction. Each faction has its long-term goal to keep it busy, but they’re also thrashing about dealing with whatever just happened and attributing it to the other factions. For the players, remember: if you cause a bit of chaos, that will usually give you time to get away. Also you know enough to pursue your own goals. If they intersect with someone else’s goals, that someone will first approach you and try to work out a deal, because acting directly against you will probably be more damaging for their plans.

- Have a Mentat or Bene Gesserit agent the PCs can consult. They start by hiring the PCs for a bit of work. That way the players can find out about the politics little by little and from information they collect themselves. Don’t infodump, don’t betray them on the first mission, let them figure out enough that they can see traps coming. The feel of this game is that you’re clever, not you’re lost. After a successful mission, have a Guild agent ask them to do some work, so they have a chance to ask their first patron about it. Build out a web of contacts.

- Start small and/or young. It doesn’t make much sense for a working, mature Mentat, Bene Gesserit and Guild Ambassador to go adventuring together but if they’re all novices-in-training, then you could totally create something like a classic D&D style party of differently-skilled adventurers who are all children of the same House, for instance – it would be wise for a noble to send his children to each of the Schools, to have some eyes and ears in each camp. Adventuring youngsters also have excuses to rub shoulders with those independent go-betweens, snoops, grifters, and semi-official smugglers who are rarely seen but often mentioned in passing during the book – not everyone is locked into the Imperial power hierarchy, and trainees still have room to adjust their positions, before they get too deeply initiated into one cult to be able to get back out. Youth is when you can recover from your mistakes, pass unrecognized, and figure out the basics of your own Grand Scheme.

…….still here? OK so there are two more factions who exist to destabilize this opening setup, who intrude before the end of Book 2, which is probably where Villeneuve’s Movie 3 will take us. Since they are external to the basic power structure of the Empire AND they’re mysterious and disruptive, personally I would keep them as NPCs only. It’s good to have some important pockets of the unknown.

Ix is a planet full of renegade mechanical and electrical engineers who skirt all the technological restrictions that the Guild and Mentats depend on. The best machines come from Ix (better than those on Richesse) and everyone uses them – ornithopters, repulsor-lift pads (useful for making lights and fat Barons hover), semi-autonomous fighting dummies, hunter-seekers (flying assassin needles with motion sensors)… They never put out a fully-functional computer but it’s clear that many of their devices would require sophisticated logic boards. But then, the religious restriction is only “Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind,” which, rather like the Islamic injunction against drunkenness, can be interpreted either as a strict ban on a whole category of products or a milder ban only against their over-use. The Ixians also dabble in conditioning and coercing people, like everyone in the Duniverse. But their efforts tend to be one-off lab experiments – ideal persuaders or seducers who are extremely good at their one function but aren’t intended to be the sort of trans-human superbeings that the Bene Gesserit, Mentats and Guild aim for.

Much of what Ix produces, makes the Guild itchy. The Guild would certainly cut Ix off from the rest of the Galaxy… except then they wouldn’t know what the Ixians were doing and they would lose their leverage to control/guide/persuade them to stay out of interstellar spaceship design. Perhaps the Guild could nuke Ix (perhaps one day it will) but for now it tolerates the Ixians, because their devices are so damn useful, because everyone wants to trade for them (which helps everyone tolerate the awful influence of Spice on their economies) and because profits are maximized when you don’t arbitrarily shut down all innovation. Still… one day they will go too far.

The Bene Tleilax or Tleilaxu are a civilization/cult/race of chemical, genetic, and social engineers. Where Ixians threaten the Guild’s monopoly on starships, the Tleilaxu threaten to create artificial Spice and, potentially, genetically-engineered Mentats, Bene Gesserit, and Navigators. They have several planets, making it harder to nuke their bases. Far worse from the Guild’s perspective, they can mimic any person in the Galaxy using their Face Dancers – engineered humanoids who can change their shape, appearance, and sex to undetectably replicate any individual. I think Face Dancers can even have children as males or females, but that’s probably best left as a mystery to discover in your campaign. Obviously, hiring Face Dancer assassins is very expensive.

They can also create clones (“gholas”) from dead cells and those clones can sometimes access the original’s memories, allowing for either functional immortality for their leaders or something like Calvin’s Duplicator Box. Perhaps in a nod to the creature’s strangely flexible morphology, the devices used to achieve all this are called Axlotl Tanks.

Then 3. Dune mashups!