Archive

Tiki’n’D2: the joy of veils

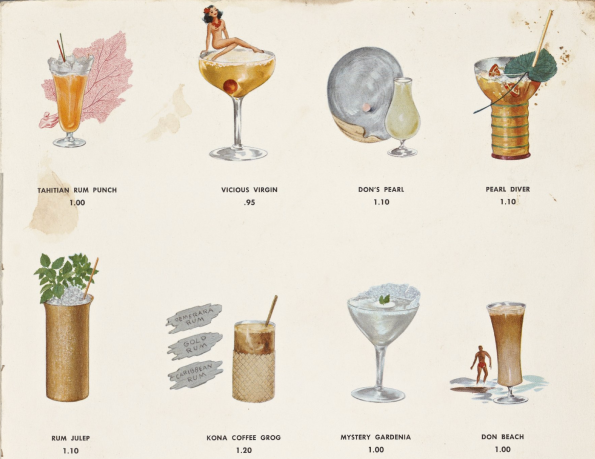

“These aren’t really drinks. They’re trade winds across cool lagoons. They’re the Southern Cross above coral reefs. They’re a lovely maiden

bathing at the foot of a waterfall.”

So a little while ago there was an article on Kotaku that sorta celebrated D&D and sorta concluded it was obsolete:

“It is he, the smiling, all-knowing dungeon master, who controls the game’s mysteries. An afterthought, players are the puppets who act out the fantasy.

“Today’s Dungeons & Dragons adventures ask more of the player and less of the dungeon master. Scenarios are open-ended. Dungeon dimensions are less particular, to leave room for players’ whimsies. On top of their race, class, alignment and stats, today’s character sheets want to know why the player adventures, and what they ultimately hope to gain. Today’s Dungeon Master’s Guild, an official D&D website that publishes anyone’s adventures and additions to the game, tells us who really owns its legacy. It was Gygax who originally fought against making the ruleset open source.”

Greg Gorgonmilk disagreed: “The general thesis seems to be that giving the GM too much control is a bad thing, as though the responsibility of the other players should go beyond their characters. This is something we see in New School games a lot and it has its strengths and drawbacks but most notably (at least for the purposes of this article) those games are not like any iteration of D&D that I am aware of.”

…Christmas 1982 I got Traveller Deluxe and Moldvay Basic from two rather distant relatives. It took a month and the help of a schoolmate to overcome the initial confusion but then I was slowly, uncertainly hooked.

One of the things that slowed me down – one of the most distinctive elements of this new way of neither exactly playing a boardgame nor exactly playing let’s pretend – was the role played by the DM. I had no exact analogue for it and all the things I did already know betrayed me one way or another.

Like a novelist, the DM holds all the secrets and knows what’s in every cave. But that’s where the novelist metaphor ends and every other part of being a novelist – narrating what the heroes do, directing their actions, revealing the inner mental lives of the characters, using multiple perspectives to reveal facets of a story – are actively harmful to playing the game. You’ve seen The Princess Bride, of course. You know how Peter Falk breaks off the narrative to tell the kid “it’s OK, she doesn’t die here. We can stop if it’s getting too scary”? When I saw that I’d already DM’d just a little and I knew it was terrible form – threatening to take the experience away because the kid didn’t like it or it was getting too intense, deferring to the writer as ultimate guide. No. It canceled the stakes, brought the players’ engagement up short, stopped them making the decisions that could ruin them.

The other frequent metaphor, that of a referee, was equally misleading – a strictly neutral ref might adjudicate in a game of skill or luck but the DM’s thumb could never be free of the suspicion of tipping the scale. I was just getting to the age where I could recognize that answering “I got you” with “did not!” was foreclosing the game I had been invited into and replacing it with an argument nobody wanted. So for our fledgling play group it was, I think, a great but only semi-deliberate act of trust to assign the position of DM with its peculiar double responsibilities of playing the opposition and refusing to advocate for them. Never to pull punches, but also to telegraph the cues a skillful player would use to avoid getting punched. If we didn’t quite understand the awesome responsibility those first few times, we soon found out as we played with capricious, cruel and uncommitted DMs after school – people who were intrigued enough to try but not engaged enough to try hard.

I recently got to play Braunstein with Dave Wesely (+Zach H’s photo is of B4: Piedras Marrones) and I was startled by how lightly – almost invisibly – he refereed. Braunstein 1 is pretty much a statless larp in which all the scenario building is front-loaded in the character packets. Each player gets a role, a set of objectives and something to trade with, and then the game begins and people wander around learning puzzle pieces from each other, finding out why their objectives are complicated, negotiating and cajoling and threatening. Dave’s job, once it was on was, I’d say, maintaining simultaneity. Letting the room know when player-initiated events had happened (but not that they were player-initiated). Running NPCs’ responses when needed, although I hardly saw any, there were so many players.

It made me think hard about the players’ responsibilities. They were there to make their characters spring to life, sure. They needed to play their parts, pursue their objectives (on which others’ objectives depended), cause trouble. But they absolutely were not there to advance a story. There was no pressure to keep one foot on either side of the fourth wall, to have any consciousness of plot or structure or opportunities for character development. Their responsibility was to live as fully and inventively as possible inside the space.

Big deal. So far so trad. Where’s the Tiki?

1933; Prohibition ends and ERB “Don” Gantt opens a bar/restaurant called Don the Beachcomber, casting himself in the title role, sporting colonial slacks and an Indiana Jones hat. This new bar combines several innovations into a new formula that will transform American drinking culture. Most of the elements are not new but, (to belabor a metaphor) they make a new synthesis, which flourishes in the post-Prohibition environment.

And the new thing is mystery. The exotic.

Nobody wanted mystery in their drinks during Prohibition (or again during the war), when the provenance of spirits was a major concern because the bathtub stuff could cripple you. The bartender’s job was to shake clean mixes in plain sight from imported bottles displayed proudly over the bar. The classic 20s cocktails – the Martini, Manhattan, Negroni – were simple 2 or 3 ingredient drinks that showcased the qualities of individual ingredients. Bond drinks vodka Martinis because their crystal clarity makes it hard to conceal drugs. Cloudy sours – the Rickey, Sidecar, Collins and so on – might make it harder to identify a particular doubtful spirit base but to be well made, they need the best ingredients. Trust in the bartender was strictly limited and customers often led the effort to find and share new mixes. When Erskinne Gwynne “crashed into” Harry’s Bar in Paris with his Boulevardier Cocktail, he was part of a rowdy emigre drinking crowd that was inventing and publishing its own cocktails and relying on Harry to spin the bottles and keep count.

Don takes a sharply different tack. Instead of branded bottles on the bar he sells potions from a menu, made with a wild variety of under-specified rums and a bunch of secret “Don’s mixes,” which stay secret and have to be distributed from HQ as the franchise takes off and Beachcombers spring up across the US. The rum is suspiciously cheap and it shows amazing variety exactly because it’s less controlled, standardized and valorized. It comes from a plethora of small producers. During Prohibition it had run into Florida under the radar, was unpredictable and a little bit dangerous: an irreplaceable and explosive fuel for the Harlem Renaissance, the low-rent end of the 20s’ roar.

So when Don puts his elixirs on the menu with names like Tropic Breeze and Zombie Punch he’s offering his customers a taste, not of what they expect, what they’ve helped design, but of forbidden pleasures they’ve heard of but been afraid to try for the past 14 years. And he doesn’t shake them in the open, he makes them with an electric blender in the back bar and brings them out in ornate, opaque mugs, discreetly veiled by fruit garnishes and umbrellas.

You don’t ask what’s in them. Even the bartender doesn’t know. So you get on with playing your role up to the hilt, causing trouble, taking no responsibility for what’s going on with the service because you don’t have to know how it works. And that’s how it opens up a space for magic – there’s that little bit of a surrender to fate.

So I’m not here to say which approach is better. I love Martinis and Pearl Divers equally – I even mix them sometimes. It occurs to me that Gwynne probably represents a free sharing OSR blogger more than a storygamer, while Don was unquestionably into monetizing his intellectual property even more than Gary but I guess that goes with being Phandaal, legendary creator of lost arts and inspirer of cargo cults. What I do take issue with is the idea that the player is an afterthought in either approach. It’s all set dressing for the players and the things they choose to do.

RETCON: time (the inevitable tyrant) got in the way of this post being as good as it could have been. Happily I can edit posts later, so here is Jeff’s necessary weigh-in: don’t go gently into that good night that is the game ending for your character. This is what I failed to say: the rules are good and important but they’re not as important as the game at hand, just like your lovingly created world is important but ultimately less so than moments at the table.