Pre-Raphaelite Arthur part 2

Last time I talked about some reasons why I think 19th century versions of Arthur have been ignored in RPGs. The core of my interest is really the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – a loose collection of British artists and writers who shared a certain artistic sensibility in the middle of the 19th century, who promoted a distinctive view of Britain’s medieval history and who shared an enthusiasm for rich decoration; hand-worked, non-industrial art; and thin, red-haired women. They mostly knew each other, at least through the critic John Ruskin, who promoted their exhibitions, and William Morris, who did everything – fine and decorative arts, writing, organization, editing, promotion, sales… You could decorate your whole house with Morris’s work, from the furniture and wallpaper to the books on the shelf and painting in the study. So what happens if we actually look at them?

Well, there’s really a bunch of subjects all tied up together here:

– the differences between Tennyson’s 19th century Arthur stories and Malory’s 15th century ones;

– the visual storytelling of the Pre-Raphaelites and its influence over our “look and feel” for Arthurian type stories;

– the whole idea of the “medieval world” as a setting.

Taking the last part first, both the concepts of a medieval and a renaissance period were invented after the fact – first in the mid 16th century, to differentiate the then-improving present from the crappy past, and then in every time period since, to support narratives about the present. The idea of the medieval is based on a story that says Europe (and therefore “civilisation”) had been glorious under the Roman Empire but then it was plunged into darkness on September 4, 476 AD by the Goths, and there is stayed as a cesspool of disease and depravity for a thousand years, mired in a “middle age” between two golden ages. Roman civilisation was finally “reborn” (“re-naissance”) – in Italy, of course – and could first be recognized in the form of a new naturalistic skill in painting.

This story started as an art history theory and spread to other disciplines. The idea that visual arts can offer a barometer for cultural sophistication is central to the whole concept: if people can paint with perspective then, art critics reasoned, they must have maths, rationality, and improving public health. And to this day, hardly anyone really questions that equation. By the late 18th century Edward Gibbon, having noticed that early Christian art had turned Rome away from perspective and naturalism, blamed the spread of Christianity for screwing up the Roman Empire and depriving the world of working sewage systems.

The period of “rediscovering” ancient Roman glories and learning how crap Europe had been without them is obviously tied up with the 17th and 18th century “Enlightenment” movement (a term actually used by people at the time!), which can perhaps be summed up in the sentence; “now we’re no longer superstitious medieval idiots and we can finally think for ourselves, how shall we take charge of the world?” Maybe less obviously, this same period also saw European colonialism and early imperialism spread across the world. In the late 17th century, Europeans started thinking of themselves as superior not only to their medieval ancestors but also to other peoples – in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. The similarities in developing attitudes regarding the medieval past and the Orient are… striking, such that by 1800 I don’t know if either idea really makes sense without the other – Orientalism is the practice of viewing Asians as medieval and anti-medieval prejudice is a kind of Orientalism. In the second half of the 18th century European critics start calling Indian society “medieval” and “child-like” – an attitude that only strengthens right up through WW1.

But then in the 19th century, several things come together to give this Enlightenment confidence a bit of a jolt (outside France, at least) and swing the pendulum… somewhere else. First the French Revolution, which started by killing aristocrats and ended by crowning a commoner, made a lot of aristocratic rich Brits rather nervous. The rationalist French Republic had collapsed into a military dictatorship, just like the Roman Republic had (Napoleon even had a habit of dressing up as Julius Caesar, just in case you might have missed that historical echo). After Napoleon’s capture in 1815, “Romantic” movements started to question the Enlightenment’s confidence in engineering every aspect of the world and humanity – if it led to dictatorship, maybe it wasn’t so desirable? The best-known expression of this counter-movement is probably Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, with its over-reaching scientist and dispossessed, sympathetic “monster” offering a pretty transparent critique of turn-of-the-19th-century society. In visual art there’s less imitating Greece and Rome, more striking dramatic poses and expressing (horny, restless, heroic) emotions.

Right: Anne-Louis Girodet: Chateaubriand Meditating on the Ruins of Rome, 1808. Thoroughly Romantic. Note how his powerful meditations ruffle up his hair, giving him a windswept and interesting air. He’s thinking “even mighty Rome could not escape the inevitable dissolution of all worldly majesty.”

Second, there’s a rise in nationalist movements all over Europe. Nationalism is a sort of religion that claims the people of this territory are different from and better than those next door. This territory’s people must therefore rule themselves independently and define what makes them so awesome. That awesomeness almost always comes from the incalculable past, maybe the beginning of time itself, and is generally found in the soil, the blood, and the spirit of the people. It tends to suddenly burst out in revolutions, where you can finally see it waving free and shocking the formerly powerful but now degenerate imperialists who were holding it back.

Third, there’s a big Gothic Revival movement over much of Northern Europe and especially Britain after about 1850, which strangely rehabilitates the medieval, bringing it into the growing nationalist mythologies.

Late 19th century buildings in Germany, Canada, and England. Source.

What? Weren’t we just clawing free of our medieval constraints? Well,

(1) those primordial nationalist roots are eternal, not constrained by the changes of time, so it’s hard to be proud of your Nation in perpetuity while also being ashamed of it before a couple of hundred years ago, and

(2) I have a sneaking suspicion it is not accidental this rehabilitation happens at the same time that “scientific” racism becomes fashionable. During the 19th century, discourses of colonialism get more racialized (at least in Britain, France, and Germany), so that colonized people are seen not so much as “backward” but as “fundamentally inferior.” Scientific racism allowed for a decoupling of anti-medievalism from colonialism, i.e. it allowed you to be both Orientalist and enthusiastic about the non-Roman bits of your history at the same time. And

(3) rapid industrialization was irreversibly reconfiguring the landscape and society of Britain and the British Empire worldwide, in ways that made it significantly less amenable to Romantic celebration. It turns out “rationalizing” business into Capitalism doesn’t spontaneously create a sort of neo-Greco-Roman ideal world. So a bunch of British intellectuals and aesthetes started pining for a simpler time before the Neo-Roman imperial movement began… or maybe they were just sick of Enlightenment neoclassicism, or maybe they wanted to show that Britain had always been great, even through its supposed “dark ages” before it rediscovered Italian civilisation.

If this sounds anti-progressive, yeah it is, although its proponents would insist they just wanted to be smart about progress and not simply accept whatever changes happened to be happening. The Gothic Revival movement was also often semi-self-consciously fantastical: they tended to decorate garden follies or make new building types – like railway stations – look reassuringly medieval on the outside while doing nothing to disguise their Dark Satanic Mills on the inside. When Gothic Revivalist Pugin contrasted the “best” of the medieval world (very often heavily idealized) with the “worst” of the Enlightenment – juxtaposing e.g. medieval almshouses with enlightenment Panopticon prisons, he deliberately glossed over the better comparative cases – medieval punishments and enlightenment charity like he wasn’t even trying to win an intellectual argument.

As I mentioned last time, you draw your boundaries where you want, to yield the specific effect you prefer. The Pre-Raphaelites drew their boundary right at the cusp between the late medieval (early Renaissance) and the High Renaissance, just before the church lost its near monopoly on approved subject matter for paintings. They decided that British painting had been cruelly hijacked and made to serve Classicist Italian models ever since Sir Joshua Reynolds had started up the Royal Academy of Arts, because Joshua felt that everything could be improved by adding ancient Rome – he thought painting had returned from the dark ages under the brush of Raphael and that Rubens and Reynolds himself were Raphael’s successors.

I dunno, personally I’m not totally convinced Reynolds was up to Raphael’s standard...

Sick of the Italian High Renaissance contraposto and chiaroscuro lighting that Raphael had championed, and sick of the slavish Classicism of the Royal Academy’s judges, who preferred eg. Jacques Louis David to the Pre-Raphaelites’ own Edward Burne-Jones, the Pre-Raphaelites formed a Brotherhood to celebrate the awkward poses, meticulous costume detail, and flat picture planes of the painting world that Raphael had ruined.

Their excitement about rediscovering a medieval sort of sensibility was not strictly historicist, though. They definitely said they wanted to strip away years of Enlightenment/Baroque nonsense to reveal a purer/more spiritual essence… but they didn’t want to excavate the past: instead they were interested in improving it – creating a more perfect, more authentic medievalism for their current moment. You can see the same impulse in Viollet-le-Duc’s restorations of e.g, the fortified medieval town of Carcassonne, where he harmonized the appearance of the conical roofs and added a drawbridge here and there, bringing the city, as he said, “to a complete state that may never have existed at any one time.”

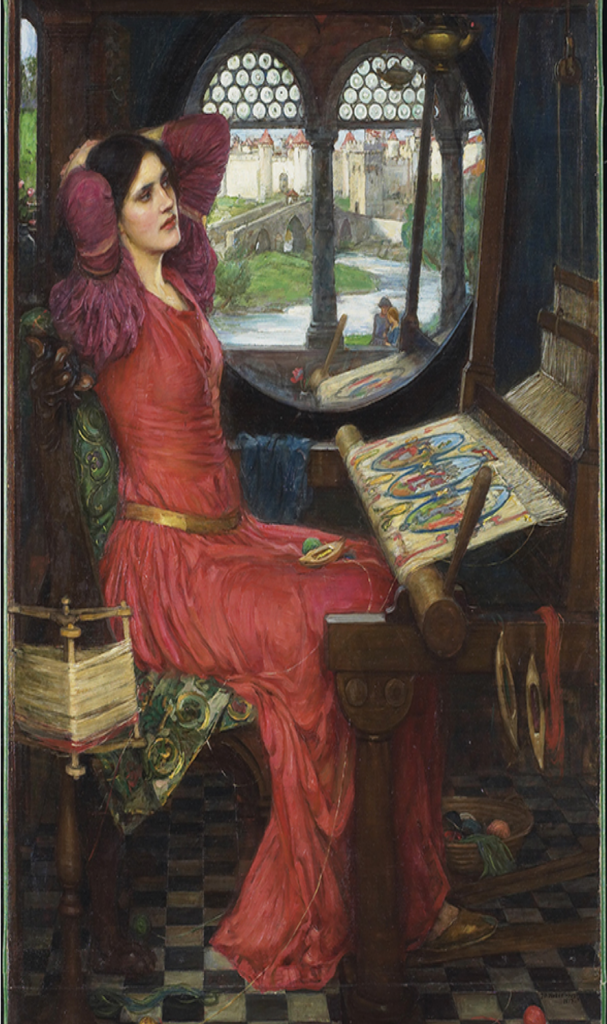

Pre-Raphaelite painter John Waterhouse puts Carcassonne in the mirror behind Elaine of Astolat (a.k.a. the Lady of Shalott), a minor character from Malory who plays a much larger role in Tennyson’s 19th century Idylls of the King. She is shown here tied up in her tapestry-wool, an apt metaphor since in Tennyson’s poem, merely by leaving her womanly position at the loom, the Lady dooms herself to death. BTW I’m pretty sure that’s William Morris’s loom, that Waterhouse’s model is posing beside.

The sheer number of Pre-Raphaelite paintings of the Lady of Shalott is daunting. Evidently, they found her to be Tennyson’s most compelling subject.

OK, so. Tennyson. When it comes to a more perfect medievalism, it’s pretty interesting that Tennyson chose Malory’s Arthurian myths rather than, say, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales as his window into the period. Both are works of literature, so neither should really be trusted as guides to their originating societies but… Chaucer drew portraits of many of the social types of his times, he was interested in peasants and millers and landowning ladies, alongside the more conventional knights and squires. He wrote about their concerns regarding marriage and wealth and poverty and birth and death and farting. Malory’s world, on the other hand, only really consists of knights and ladies, knights and quests, knights and false robber-knights. Tennyson’s main contribution is to refocus Malory from the knights onto the ladies’ experiences, retelling the stories as dramas of women and presenting those women as products and victims of their station. When people talk about the miserable state of Victorian gender politics, chances are they have Tennyson lurking in the back of their minds.

So when Sir Lancelot-the-Heartthrob uses the “favour” of Elaine of Astolat to joust and gets injured, all to defend Guinevere’s reputation, what Tennyson writes about is Elaine falling in love with Lancelot while she tends his wounds, Lancelot ignoring her (for honour and because secretly he loves Guinevere), and Elaine dying of a broken heart. Note, even though this is Elaine’s story, her agency in it is restricted to loading herself into a boat and clutching an accusatory love letter to Lancelot, so that her dead body drifts down to Camelot and her story is finally heard posthumously, causing the court to weep.

…if you were writing an RPG about Chaucer, you would need massive sourcebooks about all the various walks of life and society. You’d want varied character classes and backgrounds etc. An RPG about Malory (other than Pendragon) might be best served as a limited-frame storygame, where the players take the two roles of Knight and Lady, and the quest objects and background are generated ad hoc. A game based on Tennyson’s Idylls of the King would probably be single-player storygame (the Lady), with the object of getting Arthur to understand anything about your life, with nothing but flowers to communicate your meaning.

Hey look, there’s another set of roundels like the ones she was weaving, only this time they’re quilted.

Gustav Dore (not a Pre-Raphaelite) also illustrated Tennyson’s Elaine, in a style that makes her look less tragic and more consumptive.

Aside: I think (and I expect I’m in the minority here) there’s a recognisable German-ness to the Dore illustrations. I add them here because I think the contrast with the Pre-Raphaelite depictions really points up how distinctive the Pre-Raphaelite vision is: the expressions and attitudes of the women, the attention given to their material culture, cloth, embroidery, jewelry, etc. and the equal attention given to “foreground” and “background” elements all suggest a larger world that extends beyond the canvas – far more, I think, than Tennyson’s poems demand.

Of course, if romantically-painted Victorian women aren’t swooning tragically, they’re vectors for sin and witchery… which I have to say, the Pre-Raphaelites really enjoyed. The villainous old gossip Vivien follows Merlin to a remote place across the sea and seduces then curses him, taking him away from Arthur’s side so that Arthur can enter his tragic final phase.

Morgan le Fay, Arthur’s witchy sister, when painted by Frederick Sandys embodies all sorts of exotic dangers, suggesting a much wider world than Malory knew:

Birmingham Museum’s label (as recorded on Wikipedia) notes that Morgan le Fay is shown “in front of a loom on which she has woven an enchanted robe, designed to consume the body of King Arthur by fire. Her appearance with her loose hair, abandoned gestures and draped leopard skin suggests a dangerous and bestial female sexuality. The green robe that Morgan is depicted wearing is actually a kimono” – so, still intimately involved with cloth and weaving, but this time weaving Arthur’s downfall!

There’s another aspect to this layer of Arthuriana, though, that I think is part of that unavoidable frame the 19th century hangs around our vision of the past. Note the Egyptianate figures on the wall behind her, the vaguely Indian-looking statuette, the magical devices on her gold dress. Also, check out the spear that wicked King Mark uses below to strike down Sir Tristram in Ford Madox Brown’s contemporary Arthurian painting, the death of Tristram/Tristan:

Where did King Mark of Cornwall get a Chinese (or Japanese?) spear? Is that an Indian dagger in his belt? What about the Turkish (or Persian) designs on the curtain behind him? There’s a clear Orientalist presence in these paintings – certainly around the villains (the heraldic Bezants that identify Mark as Cornish were supposedly gold from Byzantium paid to the Saracen for Richard I’s ransom, so they’re Oriental twice over, while still being Cornish…). But even the very unvillainous Lady of Shalott’s death-shroud in Waterhouse’s painting, above, suggests an Indian Chintz, the subject of London’s great 18th century Oriental fashion craze (which BTW started that neo-Gothic trading palace, Liberty’s of London – purveyor of William Morris fabric prints).

I think the intention of this Orientalism is probably atmospheric rather than ethnist or strictly imperialist – my sense is that the pre-Raphaelites’ perfected medieval world contained the riches of the Orient, that in our inadequate history only became visible to the British around the time of Elizabeth I. The moral lessons they sought to draw from Arthurian legends demanded setting in silks and jewels – like the ones from an ancient crown that Tennyson has Arthur distributing to his jousting champions.

As for that famously shiny armour, about 10 years after the Pre-Raphaelite painters made their mark on Arthur, a (sometimes) Pre-Raphaelite photographer added hers: Tennyson invited Julia Margaret Cameron to create another illustrated edition of his Idylls of the King in albumen prints.

Cameron used whatever props she could assemble for her photos. Here, Arthur and Lancelot are wearing Crimean War cavalry helmets, a glancing reference, perhaps, to Tennyson’s most famous poem. Or maybe there were just a lot of them lying about in the 1870s. Her Death of Arthur could be the prototype for the final departing boat shot in Boorman’s Excalibur.

I don’t think Boorman’s Excalibur is really a neo-Pre-Raphaelite film, BTW – it’s pretty clearly Wagnerian – but it’s hard not to see those cavalry helms and the very shiny knights cantering through the window of Burne-Jones’s Laus Veneris,

reflected in Boorman’s ultra-high gloss, vaseline-glowing armour:

Final aside: I note that Liberty’s of London gets a credit at the end of Excalibur for “ethnic jewelry.” If that’s not a nod to the Pre-Raphaelites, I don’t know what is.

Interesting, before I read your discussion of that Ford Madox Brown painting, I immediately thought it looked eastern, probably Japanese. The spear is part of it, but the main thing is King Mark, who looks like he’s stomped out ofa samurai woodcut. I think it’s those furious wide eyes.

My first thought (again before I read on) was that there was some sort of pastiche (either west to east or east to west) going on there.

Sorry, I meant a samurai woodblock print. While I’m sure there is such a thing as a “samurai woodcut” somewhere, that’s not what I had in mind.

That’s a really good point – there is a book on Pre-Raphaelite Orientalism that I haven’t read yet, because of course they also did a bunch of overtly Orientalist art. I’m really intrigued by how they didn’t seem to put Arthur in a separate bucket. I’m not sure what that does to Edward Said’s argument that Orientalism is a “deliberate exteriority” or “estrangement” from the subject of the East

https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/book-the-pre-raphaelites-and-orientalism.html